Yiddish isn't just a language. It's a map of where we've been — the shtetls and back alleys, the kitchens where soup boiled for hours, the marketplaces where deals were struck with a handshake and a shrug. It's the music in our sentences, the comedy in our curses, the tenderness in a word like bubbeleh.

When you listen to Yiddish, really listen, you hear the footsteps of a thousand years. You hear the Hebrew prayers woven into Germanic grammar, the Slavic words borrowed from neighbors who sometimes welcomed Jews, sometimes didn't. You hear the sound of survival itself — a language that learned to bend without breaking, to carry sacred texts and street wisdom with equal reverence.

It once wrapped millions of lives like a warm coat against the cold. You could walk from Warsaw to Vilna to Odessa and never be out of earshot of it — merchants haggling, children playing, lovers whispering on park benches. In the great cities of Eastern Europe, Yiddish was the soundtrack of daily life. It filled the air in Kraków's Kazimierz district, where yeshiva students debated Talmud late into the night. It echoed through the narrow streets of Prague's Jewish Quarter, where Rabbi Loew was said to have breathed life into the golem.

But Yiddish wasn't confined to the famous centers. It lived in countless small towns — the shtetlekh — where everyone knew everyone else's business, where the shadkhen (matchmaker) was as important as the rabbi, where Friday afternoon brought the sweet panic of Sabbath preparation. These weren't quaint museum pieces; they were vibrant communities with their own newspapers, theaters, political movements, and literary traditions.

The Bund organized workers in Yiddish. Poets like Morris Rosenfeld wrote about the sweatshops of New York in verses that could make strong men weep. I.L. Peretz crafted stories that found the sacred in the everyday, while Sholem Aleichem created Tevye the Dairyman, whose conversations with God became the foundation for Fiddler on the Roof. This was a language of high culture and street smarts, of mystical speculation and practical jokes.

The world tried to erase it. The Holocaust silenced millions of voices — not just the speakers, but the children who would have learned mame-loshn at their grandmothers' knees, the poets who would have written the next generation of verses, the comedians who would have found new ways to laugh at life's absurdities. In three short years, the Nazis and their collaborators destroyed what had taken a millennium to build.

The numbers tell part of the story: before World War II, roughly 13 million people spoke Yiddish. By 1945, that number had been cut by more than half. But numbers can't capture the silence that fell over places like Białystok, where the great Yiddish poet Abraham Sutzkever once walked the streets composing verses in his head. They can't measure the weight of libraries burned, manuscripts lost, entire dialects wiped out when their last speakers were murdered.

Yet even before the war, Yiddish had been fighting for its life. The Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) encouraged Jews to speak the languages of their host countries. Zionists promoted Hebrew as the proper language for a reborn Jewish nation. Socialists argued for the international solidarity that came with learning Russian or Polish or German. Young people in Warsaw and Budapest and New York increasingly saw Yiddish as the language of their parents' backward past, not their own modern futures.

Immigration scattered the rest, and assimilation taught children to trade mame-loshn — the mother tongue — for the cleaner, safer English of the New World. The story repeated itself in tenements across the Lower East Side, in the Jewish neighborhoods of Chicago and Philadelphia, in the refugee communities of Australia and Argentina.

Parents made heartbreaking calculations: speaking English meant better jobs, acceptance, a chance for their children to become "real Americans." Speaking Yiddish marked you as foreign, as green, as someone who hadn't yet learned to belong. Children translated for their parents at the doctor's office, at school conferences, at government offices — and in the process, they became the bridge between two worlds, carrying enormous responsibility on young shoulders.

The shame ran deep. Second-generation immigrants often refused to teach Yiddish to their own children, believing they were doing them a favor. Why saddle them with the language of persecution, of poverty, of otherness? Better to let them grow up fully American, fully integrated, fully safe.

But something was lost in translation. The specific humor of Yiddish — its ability to find the ridiculous in the tragic, to express love through gentle mockery, to pack entire philosophies into a well-timed oy vey — couldn't quite survive the journey into English. The intimacy of Yiddishe expressions, the way they wrapped around you like your grandmother's arms, got replaced by more proper, more distant ways of speaking.

But Yiddish is stubborn. It still laughs in Hasidic schools in Brooklyn, still sings in klezmer bands from Montreal to Melbourne. In Borough Park and Williamsburg, in Antwerp and Jerusalem, children still grow up with Yiddish as their first language. They may learn English or Hebrew or French for the outside world, but at home, around the Sabbath table, in the beis medrash (study hall), Yiddish remains the language of the heart.

The Satmar, Bobov, Belz, and other Hasidic communities have become the unlikely guardians of a language that secular Jewish intellectuals once championed. They've preserved not just the words, but the entire cultural ecosystem that gives those words meaning. In their world, a rebbe is still a figure of immense authority, a ba'al tshuveh is still someone to be celebrated, and a shidduch is still arranged with the care of a diplomatic negotiation.

Meanwhile, a different kind of revival is happening in universities and community centers, in Yiddish summer programs and online courses. Young Jews who never heard the language from their grandparents are learning it as adults, hungry for connection to a heritage that almost slipped away. They're reading Bashevis Singer in the original, watching Yiddish theater productions, even writing new poetry in an ancient tongue.

It hides in our English — in schlep, kvetch, schmuck — little smuggled treasures from another time. These aren't just loan words; they're cultural ambassadors, carrying with them entire ways of seeing the world. When you schmooze, you're not just making small talk — you're engaging in the particularly Jewish art of building relationships through conversation. When something is schlocky, it's not just cheap — it's cheap in a way that shows a certain disregard for quality that would make your grandmother shake her head.

The influence goes deeper than vocabulary. The rhythms of Jewish-American comedy, from the Catskills to Seinfeld, echo the cadences of Yiddish storytelling. The way Jewish-Americans ask questions by making statements ("You're going out in this weather?"), the tendency to answer questions with questions ("Why do you want to know?"), the art of the perfectly timed pause — all of these trace back to Yiddish speech patterns.

Even Jews who never learned a word of Yiddish often carry its gestures, its facial expressions, its particular way of shrugging that says simultaneously "what can you do?" and "life is absurd but we go on anyway." This is the phantom limb of a severed language, still making itself felt in the body language of its former speakers' descendants.

To speak Yiddish today is to speak to ghosts and to promise them you remember. Every oy, every nu, every rolling kh in the back of your throat says: we're still here. The language lives, and so do we.

When you say zol zayn mit mazl (may it be with luck), you're invoking the same blessing your great-grandmother whispered over her children. When you call someone a mentsch, you're using the same word that once distinguished the decent from the merely human in the moral universe of the shtetl. These aren't museum pieces; they're living prayers, breathing connections to people who loved and worried and hoped in this language.

The ghosts we speak to aren't just the victims of the Holocaust, though they're certainly among them. We speak to the alte babeh who saved every penny to bring her family to America, to the young revolutionary who believed Yiddish could be the language of international socialism, to the comedian who made audiences laugh until they cried at the plight of the immigrant experience.

In choosing to learn Yiddish, to speak it, to pass it on, we make a radical statement: that some things are worth preserving not because they're useful, but because they're beautiful. Because they connect us to people we've never met but somehow know. Because they remind us that languages aren't just tools for communication — they're repositories of dreams, vessels for ways of being human that shouldn't be allowed to disappear.

The language lives, and so do we. In every Yiddish word we speak, we resurrect not just vocabulary but an entire civilization's way of seeing the world. We keep faith with the dead and plant seeds for generations yet to come. A shprakh iz a diyalekt mit an armey un flot — a language is a dialect with an army and a navy, goes the old saying. Yiddish may not have armies or navies, but it has something perhaps more powerful: the stubborn refusal to be forgotten, and the love of those who insist on remembering.

Until we meet again, let your conscience be your guide.

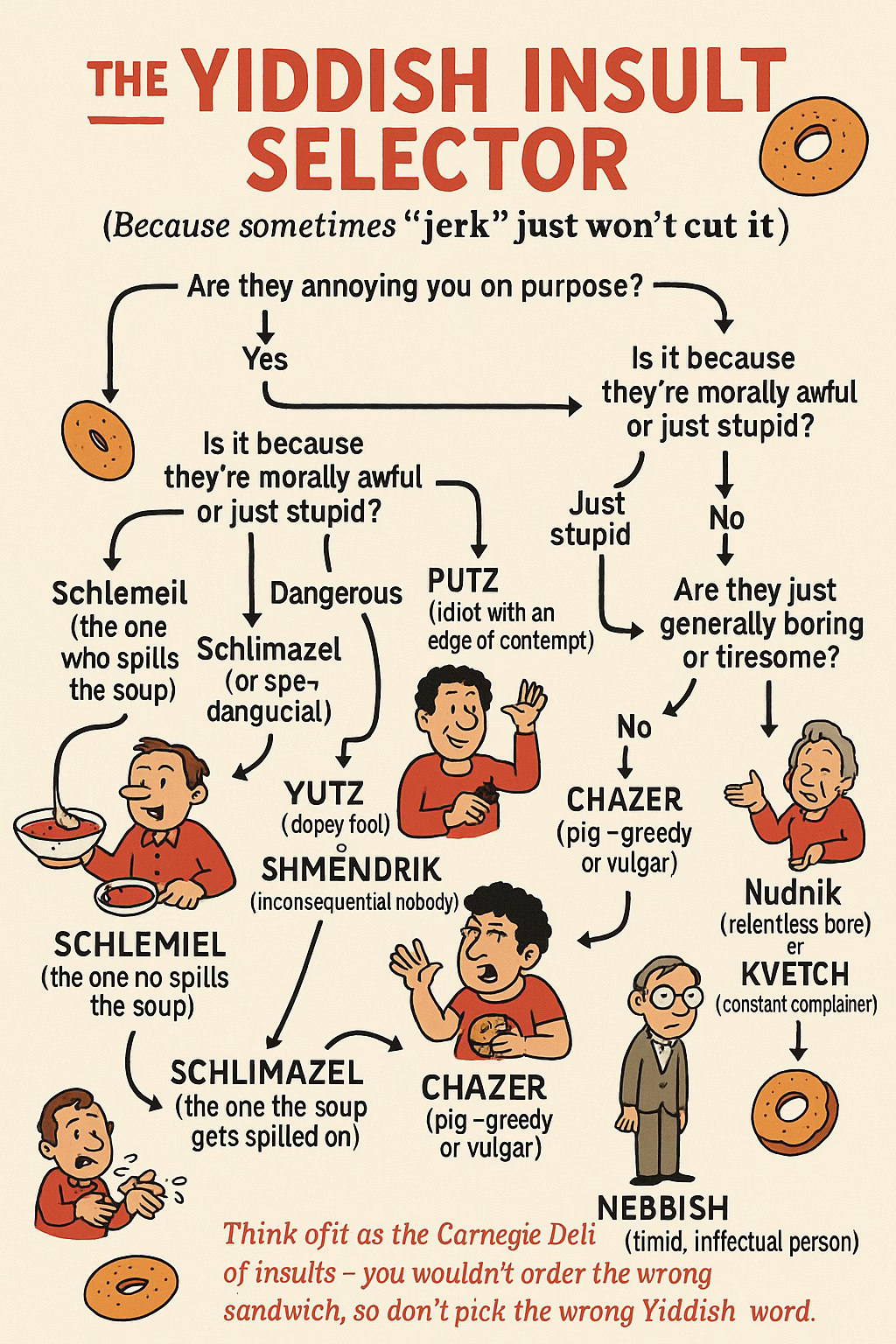

Two of my favorite words are Putz and Schmuck...

Back when I worked for the Strand Bookstore (circa early 1970s) one of my favorite Strand characters was the obsessive book maven Joe Kupic. In his world there were only two kinds of people: Putz's and Schmucks.

I kvetch, therefore I am!