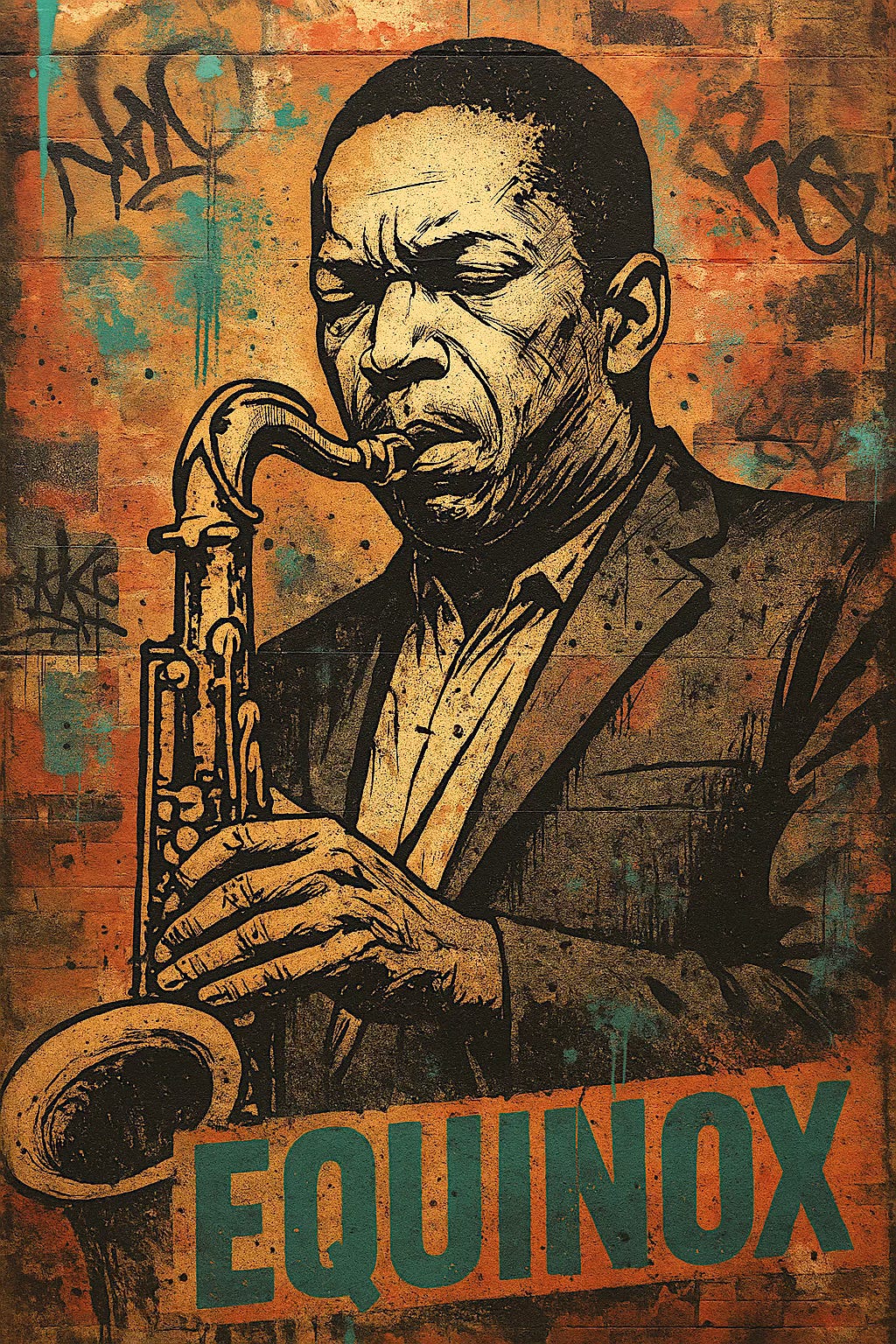

“Equinox” stands out as one of Coltrane’s most enduring compositions for several reasons that connect directly to his artistic evolution.

The piece, recorded for his groundbreaking 1960 album Coltrane’s Jazz, represents a perfect bridge between his hard bop roots and the modal explorations that would define his later work. Built on a simple but haunting minor blues structure, “Equinox” demonstrates Coltrane’s ability to find profound depth within seemingly straightforward forms.

What makes it particularly unique is its hypnotic, almost ritualistic quality. The melody moves in a slow, deliberate arc that feels ancient and modern simultaneously. This wasn’t typical blues playing; Coltrane stripped the form down to its essence while maintaining an unmistakable spiritual gravity. The piece has an incantatory power that foreshadows the spiritual direction his music would increasingly take.

The composition also showcases Coltrane’s genius for creating vehicles that other musicians could inhabit completely. McCoy Tyner’s playing on the original recording adds layers of harmonic sophistication without disturbing the piece’s meditative core. The way the rhythm section breathes with the melody rather than simply accompanying it was revolutionary for its time.

“Equinox” became a jazz standard precisely because it offers infinite possibilities within its deceptively simple framework. Musicians from different eras and styles have found new meanings in it, from free jazz explorers to contemporary players. Its modal implications allow for both inside and outside playing, making it endlessly renewable.

The title itself suggests balance and transition, themes central to Coltrane’s artistic journey. He was moving from one musical world to another, and “Equinox” captures that pivotal moment perfectly.

“Equinox” emerged during one of the most crucial transitional periods in jazz history, and understanding its importance requires examining both its musical architecture and its cultural moment.

Musically, the composition operates on multiple levels of sophistication. While superficially a minor blues, Coltrane altered the traditional 12-bar structure in subtle but significant ways. The melody doesn’t follow conventional blues phrasing; instead, it unfolds in long, sustained notes that create an almost suspended sense of time. This approach was radical in 1960. Most jazz musicians were still working within bebop’s rapid-fire harmonic changes, but Coltrane was already moving toward the modal concepts that Miles Davis had begun exploring on “Kind of Blue.”

The harmonic foundation of “Equinox” is deceptively complex. The piece stays largely in C minor, but Coltrane implies harmonic movement through his melodic choices rather than explicit chord changes. This creates what musicians call “static harmony,” where the emotional and musical development comes from melodic invention and rhythmic variation rather than harmonic progression. This was revolutionary thinking that would influence everything from McCoy Tyner’s quartal voicings to the entire free jazz movement.

The recording session itself, with McCoy Tyner, Steve Davis, and Elvin Jones, captured a band in transition. Tyner had just joined Coltrane’s group, and you can hear him finding his voice within Coltrane’s vision. His comping on “Equinox” avoids conventional bebop chord voicings, instead using fourths and fifths that create an open, ambiguous harmonic space. This approach would become central to modern jazz piano.

Elvin Jones’s drumming on “Equinox” deserves special attention. Rather than playing time in the traditional sense, he creates waves of polyrhythmic energy that surge and recede beneath the melody. This organic, breathing quality in the rhythm section was unprecedented. Jones wasn’t just keeping time; he was creating an environment, a sonic landscape that the soloists could explore.

The spiritual dimension of “Equinox” cannot be overlooked. The title refers to the moment when day and night are perfectly balanced, a concept with deep spiritual significance across cultures. Coltrane was beginning his serious exploration of world religions and spiritual practices during this period. The meditative quality of “Equinox” reflects his growing interest in using music as a spiritual practice rather than mere entertainment or even artistic expression.

This spiritual aspect manifested in the way Coltrane approached soloing on the piece. Rather than the virtuosic displays of his earlier work, his solo on “Equinox” builds gradually, with each phrase growing organically from the previous one. He uses space and silence as musical elements, something relatively rare in jazz at that time. The solo has an searching quality, as if Coltrane is using his saxophone to ask questions rather than provide answers.

The influence of “Equinox” on subsequent jazz cannot be overstated. It became a template for modal jazz composition, showing how a simple structure could yield infinite possibilities. Players from Joe Henderson to Chris Potter have recorded versions, each finding new facets within its framework. The piece taught musicians that complexity didn’t require complicated chord changes; it could emerge from deep exploration of limited harmonic material.

Contemporary musicians often cite “Equinox” as a breakthrough piece in their understanding of jazz. It demonstrates that emotional depth and technical innovation aren’t opposing forces but complementary aspects of musical expression. The piece works equally well as a vehicle for free exploration or careful, inside playing, making it remarkably versatile.

The recording also marked a shift in how jazz albums were conceived. Coltrane Jazz wasn’t just a collection of tunes but a artistic statement, with “Equinox” serving as its spiritual center. This album-as-artwork concept would become increasingly important in Coltrane’s work, culminating in suite recordings such as “A Love Supreme.”

From a technical standpoint, “Equinox” showcases Coltrane’s evolving saxophone technique. His tone on the recording is fuller and more centered than his earlier work, with a singing quality that would become his signature. He was moving away from the Dexter Gordon and Sonny Stitt influences of his youth toward a completely personal sound. The way he bends notes and uses microtones hints at his later incorporation of Eastern musical concepts.

The piece also represents a philosophical shift in Coltrane’s approach to music making. He was moving from music as dialogue (the call and response of bebop) to music as meditation or prayer. “Equinox” doesn’t argue or discuss; it contemplates. This contemplative approach would become central to spiritual jazz and influence musicians far beyond jazz, from rock guitarists to contemporary classical composers.

In the broader context of 1960, “Equinox” arrived at a moment of intense social and cultural change. The civil rights movement was gathering momentum, and African American artists were increasingly asserting their cultural identity and spiritual heritage. The dignified, powerful simplicity of “Equinox” can be heard as part of this cultural assertion, presenting jazz not as entertainment but as serious spiritual and artistic expression.

Listen to “Equinox”

Wonderful discussion of one of Coltrane's unforgettable compositions! Haunting! In a somewhat similar direction, I absolutely love his composition "Tunji."

The regularity of those gong/chords is deeply reassuring. It gives the musician the security to play adventurously.