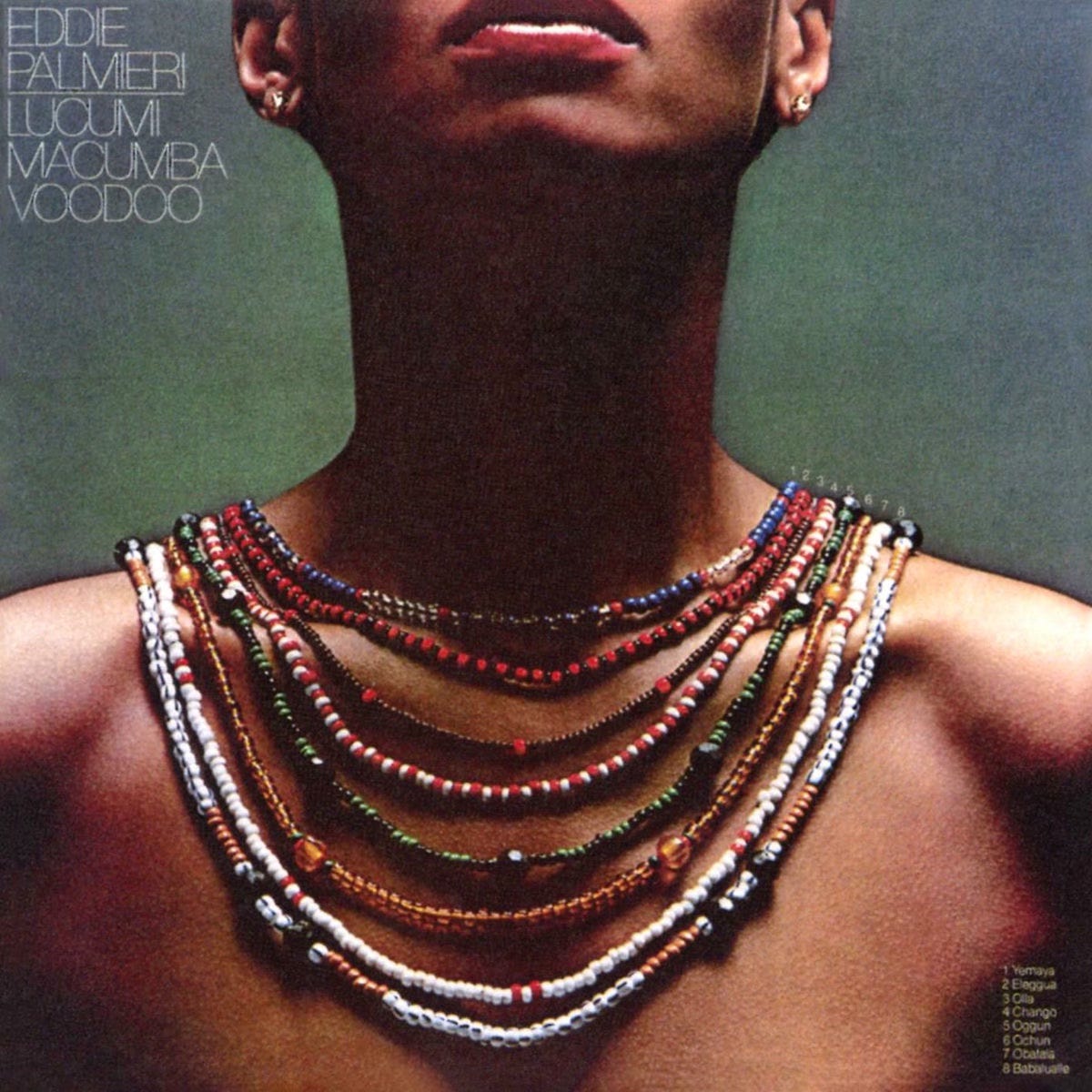

I had the honor of spending a few hours with the late Latin master, Eddie Palmieri in 1978, for a Blindfold test that was published in DownBeat. At the time, he had just released, Lucumí, Macumba, Voodoo on released by Columbia Records (specifically its Epic imprint).

By the late 1970s, Eddie Palmieri had already shaken up Latin music with records that fused Afro-Caribbean roots, jazz harmonies, political awareness, and raw street energy. He’d won Grammys, experimented with electric keyboards, and pushed salsa far beyond the dance floor.

But in 1978, Columbia Records signed him for one record. Instead of giving them a straightforward Latin dance album, Palmieri delivered something utterly different—a deep, spiritually charged exploration of Afro-Cuban ritual music. The title alone—Lucumí, Macumba, Voodoo—signaled a project grounded in the African diaspora’s sacred traditions, not commercial radio play.

Lucumí refers to the Yoruba-derived religion practiced in Cuba (Santería), with music built around batá drums and chants.

Macumba is a Brazilian term for Afro-Brazilian religious practices, often blending Catholicism with African spirituality.

Voodoo points to Haitian Vodou, with its own drumming patterns, chants, and ceremonial dances.

The album pulls from all three, weaving them into richly percussive, trance-inducing arrangements. Palmieri’s piano isn’t the flashy salsa montuno here—it’s more textural, dialoguing with an army of drummers, vocalists, and ritual instruments.

This wasn’t just “Afro-Latin jazz.” It was a deliberate preservation and presentation of sacred African diasporic traditions, unfiltered and uncompromised. Columbia probably wanted something with crossover appeal; Palmieri gave them a cultural statement instead. Though it wasn’t a commercial hit, the album became a reference point for ethnomusicologists, spiritual practitioners, and adventurous DJs. It’s still sampled and studied for its authenticity and power.

This is as much a mystical journey as an album—five major pieces stretching over 36 minutes, each a fusion of Afro-diasporic spiritual rhythms and late‑’70s grooves:

Lucumí, Macumba, Voodoo (4:38)

Spirit of Love (3:23)

Colombia Te Canto (10:08)

Mi Congo Te Llama (Medley): Prayer to Ozain / Theme to Ozain / Letras of Ozain (12:47)

Highest Good (5:28)

Palmieri assembled a veritable pantheon of percussionists, arrangers, and soloists spanning Latin, jazz, and soul realms. Here’s the lineup that turned raw myth into sound:

Percussion & Vocals: Bobby Colomby (also co‑producer)

Trumpet: Alfredo “Chocolate” Armenteros (featured solo on “Mi Congo Te Llama” and others)

Percussion & Congas: Francisco Aguabella

Electric Guitar: Steve Khan

Organ & Piano: Charlie Palmieri (Eddie’s brother)

Saxophones & Clarinet: Ronnie Cuber (baritone sax solo), George Young (alto sax/flute)

Strings (Cellos, Tuba): a small ensemble including Homer Mensch, Tony Sophos, and Tony Price

Electric Bass: Neil Stubenhaus, Francisco Centeno

Vocals (Lead & Choir): Gwen Guthrie, Frank Floyd, Lani Groves, among others; lead vocals by Luisito Ayala, plus choruses from James Sabater, Rafael de Jesus, Francisco Aguabella

Palmieri turned a major-label contract into an altar. He fused disco-era studio sheen (“Spirit of Love,” “Highest Good”) with charanga, batá, and Santería rites—no compromise, pure conviction. He handed over his charts to ritual drummers and jazz mavens—not radio programmers—letting them tell spiritual stories across shifting tempos and trance-like crescendos. Not a chart-topper in 1978 (hello, disco), but today the record stands as cosign to cultural memory, a primer for DJs, ethno‑music scholars, and anyone hungry for music that isn’t afraid to conjure.

Watch Eddie Palmieri on Night Music featuring David Sanborn

Listen to Lucumí, Macumba, Voodoo:

I am so grateful that you wrote this. You focused on what Eddie Palmieri had at the nucleus of all of his music and that is the Afro-Cuban music (which is Lucumi-Yoruba based). One of the things I love about Eddie is his juxtaposing Jazz and Afro-Cuban music. He never called it "salsa", but called it what it was. Being Afro-Cuban-American, I grew up immersed in Yoruba practice and music. Lucky for me (and my twin sister Lili) we were exposed to vast genres of music-from Prokofiev to Frank Sinatra and everything in between- Vicentíco Valdez, Celia Cruz, La Sonora Matancéra, Los Muñequitos de Matánzas, Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughn, - and a world more. It is no wonder we are both musicians. Eddie Palmieri was amongst those and as a teen (and studying the piano) I came to love Latin music. What I heard in Eddie was the major jazz influence, with the afro-cuban rhythms. This, for me, was different than the other Latin music that was popular. I would learn to play some of his music by ear - I didn't know enough yet on the piano to transcribe it. My sister's best friend in High School was the daughter of Victor Paz - phenomenal trumpet player with Eddie Palmieri. Whenever they played, we were invited. This was school for me. As my sister and her friends danced the soles of their shoes off, I was situated as close to the bandstand as possible - just to be able to see Eddie's hands. Amazing.

I use the word grateful a lot because I am. I grew up during the height of his playing and I got to see and hear it. So glad I was born when I was and came of age during what for me was a magical time - all the way around and, in spite of all the hardship the world was enduring (Vietnam, Civil Rights).

Again, I thank you for being on the pulse of all that really matters.

Barbara Anel

Bobby Colombo, Francisco Aguabella, these names were brought to me by Eddie Palmieri. Your ethnomusicological presentation of the origins and depth of what Maestro Palmieri brought to his music is outstanding. I think he is one of the stepping off points for many of today’s young masters such as Pedrito Martinez. Great article. Love it.