Several years after waving goodbye to my film school days, I found myself rubbing shoulders with the likes of Richard Dubin, a rising star in the realms of acting, producing, and directing, and Bill Boggs, the charismatic TV maestro steering the ship of Midday Live on WNEW-TV in the heart of New York. Former students of the renown acting teacher Wynn Handman, Dubin and Boggs had joined forces to conjure up TV shows and maybe even more. As a staple in the audience of Boggs' show "Midday Live," I had the golden ticket to the Green Room - a backstage wonderland where the magic of a daily talkshow unfolded right before my eyes. It was a world where the glitterati of show biz mingled with the power players of politics, each day offering a new spectacle.

This phase also saw me exploring comedy writing, occasionally contributing jokes for the show's monologues and guests, including comedy legends Chevy Chase, and, Stiller and Meara. Having my material performed by these professionals gave me newfound confidence in my ability to write something funny.

My journey as a writer was just beginning. The only joke I remember from that period that Mr. Boggs delivered in his monologue one Tuesday at Noon: It was so cold in Times Square last night that the statue of George M. Cohan, unable to give his regards to Broadway, spent the night in a massage parlor.

It wasn't exactly a knee-slapper that would have the crowds rolling in the aisles, but hey, it was a beginning - a first step into the wild, unpredictable jungle of humor.

Do You Have Anything For Me?

A particularly notable Green Room encounter was with Roman Polanski, the famed but controversial director known for his tragic personal life and distinct filmmaking style. American audiences were introduced to his films with Rosemary’s Baby. Shortly after its release, his pregnant wife, actress Sharon Tate, was killed by Charles Manson.

I admired his work as a Director, most notably Knife in the Water, a Polish film with a Jazz soundtrack, Chinatown, and Repulsion. Polanski frequently delved into intricate themes; psychological distress, paranoia, and the more sinister facets of the human psyche. However, sadly, his significant cinematic contributions were overshadowed by debates surrounding his personal life and the ethical questions his actions raised, positioning him as one of the more multifaceted and contentious personalities in film history.

The day I met him in the Green Room at WNEW-TV, we had a brief but engaging discussion about Film Noir, a favorite cinema genre. I considered Chinatown a neo-Noir and when I said that, he looked me in the eyes and said, you are correct. That gave me some credibility. At which point he paused, for dramatic effect, and then said to me, do you have anything for me? At first, I had no idea what he wanted. Drugs perhaps? And as we got into a deeper discussion of Chinatown, he kept asking me the same thing, do you have anything for me? I was a little intimated and finally said, what do you mean? A ha, a script is what he was seeking. I told him I did not have anything on hand, but I had an idea for a story about a man who figures out a way to stop time, and live in between the seconds. He suggested I write a treatment (a summary of the film), and send it to him. By the time I did have something on paper, he was forced to leave the country, and he’s never come back.

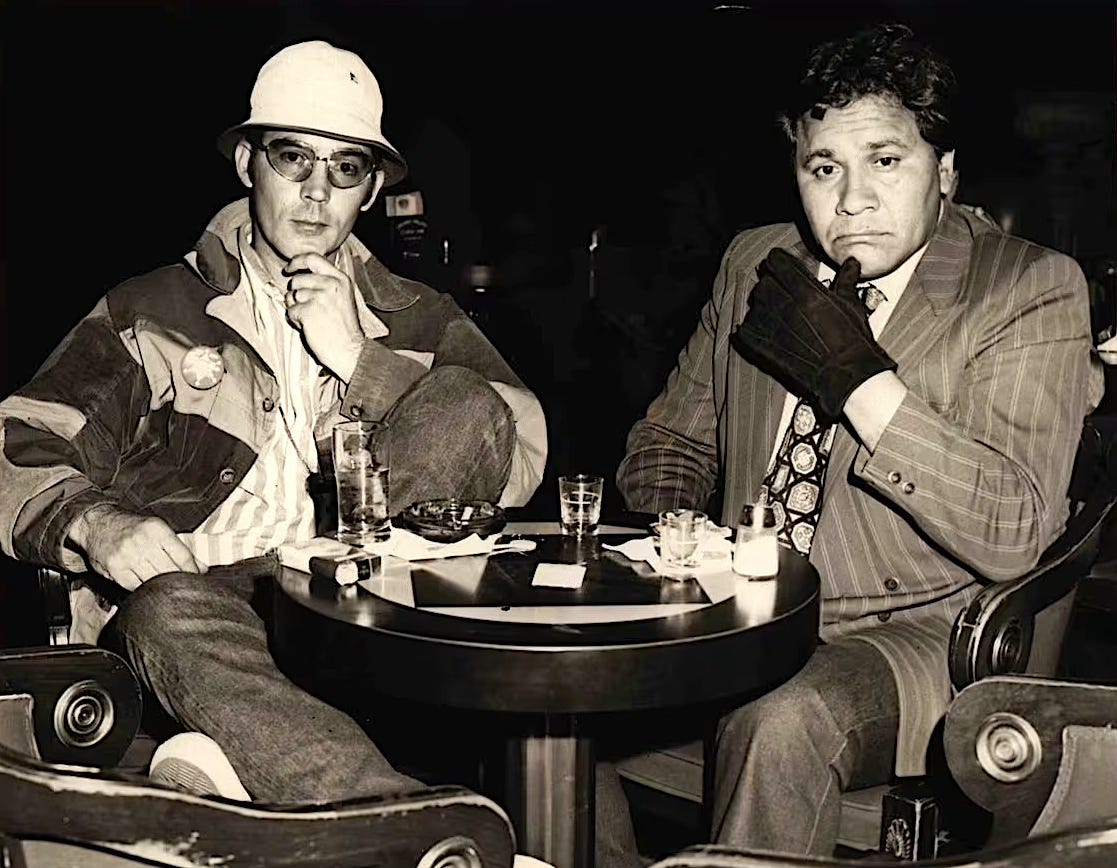

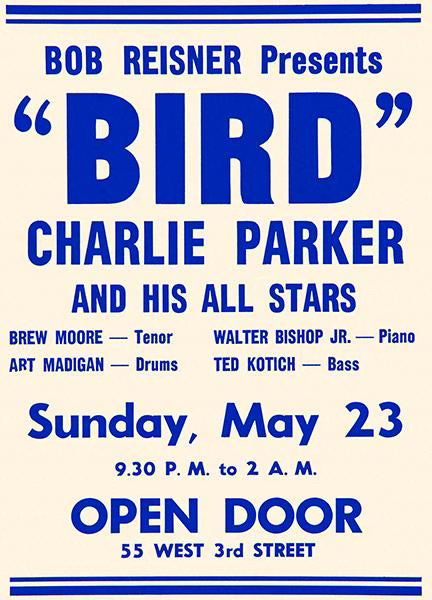

For a gathering at Bill Boggs’ apartment overlooking Central Park in 1976, we required a pianist. Dubin, a protege of jazz musician Clark Terry, reached out to CT for a recommendation. He suggested his pianist, Walter Bishop, Jr., best known for his collaborations with Charlie Parker. I was thrilled to meet Bish, having admired his recordings. Among the various celebrities at the event, some with real name value, I was particularly drawn to spending time with Bish. We connected and he revealed that no one had written about him in nearly two decades. He asked if I could interview him, and I eagerly agreed. That was the beginning of a wonderful friendship that endured until his passing in the late 90s. Bish was my first close friend in the world of Jazz.

Bird Lives!

I sent the interview to DownBeat magazine and was thrilled when they decided to publish it as, Jazz Warrior Marches On. This marked the start of my unforeseen career in music journalism beginning in February 1977. DownBeat soon asked for more articles, and I discovered that this new path was quite suitable. Within just a year, I became the East Coast Editor for DownBeat, spending almost every night in Jazz clubs and mingling with the musicians whose music had been a part of my life for years. Over the following decades, I authored hundreds of articles, interviews, and liner notes. And I came to know many important musicians.

At the same time, I was drawn to comedy writing, but opportunities to do that were very limited in New York. The idea of venturing to Los Angeles was appealing, especially with sitcom writers there reportedly earning impressive salaries. I had made some acquaintances in LA whom I could contact, so in February of '77, I decided to spend a couple of weeks there to explore my options.

While I was in the area, I thought it would be great to experience some live music, so I reached out to Leonard Feather. Intriguingly, he was already familiar with my Walter Bishop, Jr. interview, possibly due to their friendship from the Bebop era. We arranged to meet at Dante’s, a cozy club in North Hollywood. I had been following Leonard Feather's work in print, and on liner notes, since I was a kid. He turned out to be a genuinely kind person who offered encouragement for my new direction.

In LA, I also connected with Dubin’s friend Norman Steinberg, one of the writers for "Blazing Saddles" along with Mel Brooks and Richard Pryor. We discussed an article idea about the link between Jazz and comedy, given that many comedy writers and performers were former musicians.

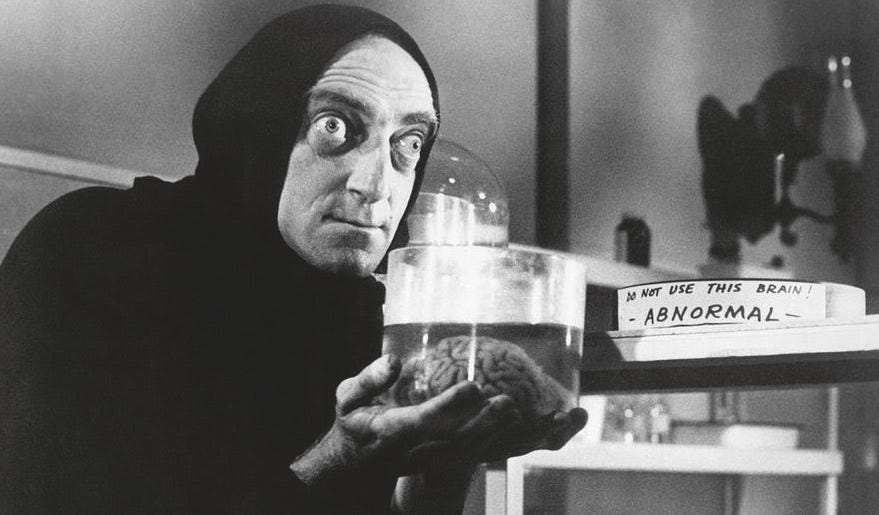

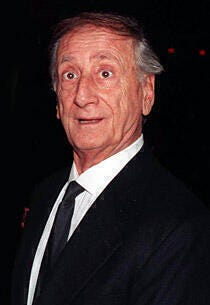

Among those he advised I meet was Marty Feldman, a renowned British actor, comedian, and writer. Feldman was renowned for his distinctive appearance,. His eyes had a wide, staring appearance, often adding a comical or startling element to his expressions. Feldman used this unique feature to great effect in his comedy, enhancing his expressive and humorous performances. Feldman was admired in the US for his work with Mel Brooks especially "Young Frankenstein" and "Silent Movie." Interestingly, back in the UK, he had aspirations as a Jazz trumpeter and even played in a band with tenor saxophonist Tubby Hayes. Eventually, he shifted his focus to comedy.

Thanks to Norman Steinberg, another generous, supportive fellow, I met Mr. Feldman at the Warner Brothers studios. The experience was surreal, arriving in a rented Ford Mustang convertible and at the gate, announcing my appointment with Marty Feldman. Our meeting, in one of the studio bungalows, was as humorous as it was enlightening, showcasing Feldman's warmth and insightfulness. Regarding Jazz and comedy, Marty revealed that for most of the time he spent in Jazz clubs, he found a parallel between 'riffing' in a comedy partnership and Jazz improvisation in a group.

During my exploratory trip to Los Angeles, thanks to Norman, I also had the opportunity to meet with former jazz musicians who had transitioned to comedy writing and performing including writers from the Carol Burnett Show, the Mary Tyler Moore Show, and the Bob Newhart Show, as well as the rubber-faced comedian, Charlie Callas.

Charlie and I convened in the coffee shop located in the basement of the Sheraton Universal Hotel, where he vividly recounted his thrilling time playing drums on the Tonight Show when he was a guest. He was a Carson favorite, and told me that Johnny aspired to be like Buddy Rich, while Buddy himself would have loved to become a stand-up comedian. Our conversation was made even more lively and entertaining by the comedian's animated expressions and humor. He brought our chat to life by creatively using a knife and fork as makeshift drumsticks, playfully drumming on the table, executing a series of drum rolls, and even tapping rhythmically on the glasses. Given the hustle and bustle of the coffee shop, practically located on the Universal lot, no one even noticed.

Unfortunately, the article I wrote about this intriguing connection between Jazz and comedy, both essentially improvisational arts, was not published. The editor at DownBeat magazine didn't find the topic “relevant.” Nonetheless, the trip gave me the opportunity to meet very cool people, and give me some idea of the entertainment business in LA.

Fear and Loathing at the Polo Lounge

In town, I went to the Polo Lounge at the Beverly Hills Hotel, known from Hunter S. Thompson's “Fear And Loathing in Las Vegas.” I thought to honor Dr. Gonzo by taking a bit of acid first. But not wanting to drive like that, I decided against it. Anyway, I wasn't after hallucinations, just a sharper edge to things. I didn't need it, though. Stepping out of the car, it was like entering a Fellini film.

But looking back at my ‘67 Mustang, I felt distinctly out of place amidst the luxury vehicles at the hotel. In LA, where your car often defines you, and in a town so focused on status, my used but not abused convertible seemed meager compared to the Mercedes’, BMWs, and Aston Martins. I was also wearing a totally unfashionable black suit, the only formal attire I owned, which led Charlie Callas to quip, “you look just like an undertaker.”

The Polo Lounge was a hive of activity, a true hotspot for big time show biz networking and deal making. The air was charged with an electric sense of significance, as if something vital was unfolding. I discreetly handed the Maître D' a five-dollar bill, and my new lifelong friend guided me to a table at the heart of the lounge. While en route, I noticed a robust, perspiring man skillfully managing two phones, simultaneously engaging under the table with two notably voluptuous women who were seated alongside him. As I settled into my seat, a midget dressed in a pink suit, was busily moving around the room with a phone, paging someone who seemed to be of real importance. More life and death business, Hollywood style.

After ten minutes of people watching, a woman seated near me with a top heavy body that looked to have its own zip code, began interrogating me in a voice loud enough to awaken Al Jolson.

“Didn’t I see you at Bobo’s party?”

I tried to hide.

“No, it must have been someone else.”

“Are you sure, you look very familiar.”

“Thank you.”

I couldn’t think of anything else to say.

“What’s your name?”

“Bret.”

“Bret?” She said my name as if it made her sick to her stomach.

“What kind of name is that? I’m sorry but you’re never going to make it in show business with a name like Bret.”

For a second opinion, she turned to a hairy chested guy with a shirt open down to the navel and a myriad of gold chains, “He’ll never make it in show business with a name like Bret, will he?”

He sized me up and down, shook his head and said, “no, change it to Alan.”

As I contemplated altering my path through a makeover of sorts, she invited me to her table for a beverage. As I drew nearer, it became clear they were escorts, blending effortlessly into the diverse and vibrant crowd of the Polo Lounge, a place known for its mix of ambitious and opportunistic individuals, i.e. hustlers. Underneath all the pretense, they were just a couple of small town girls in search of their moment in the limelight. They greeted me as if I was a pal, and generously shared Hollywood networking tips, emphasizing the right spots and times, particularly during Happy Hour with free Hors d'oeuvres. I spent almost an hour in their company after three or four martinis, they began sharing their tales, illuminating the atmosphere with vivid narratives, much like a Christmas tree coming to life with sparkling lights. Although some of their escapades involved stars, they chose to be discreet, revealing only info about their bodies and their sexual proclivities, not their identities. It was most enlightening.

And so there I was, at a crossroads—should I stay in LA to pursue a career in TV and the movies, or return to New York and become a full-time Jazz writer? Despite the opportunities in LA, I didn't feel comfortable there, a sentiment shared by many New Yorkers who have contemplated the move. In the end, I chose to return to the Big Apple, the Jazz Mecca of planet earth, never regretting my decision despite wondering, many many times, about the 'what ifs'.

My friend Richard Dubin, however, did move to LA and achieved great success for nearly fifteen years in television as a producer, director and writer on such shows as Roc and Frank’s Place.

His exit narrative vividly showcases the frenzy and avarice prevalent in the Los Angeles show business scene, offering a suitable insight into the mediocrity it represents.

Following a string of successful shows, Dubin landed a lucrative deal with the Fox Network to produce sitcoms. These types of shows, whose popularity fluctuates, are typically the product of collective effort. Regrettably, the involvement of multiple collaborators often leads to sitcoms lacking genuine humor, propped up by canned laughter. Each week starts with a table read of the script on Monday, closely followed by a team of self-appointed experts refining the jokes, punching them up, almost hourly leading up to the Friday night’s actual presentation. Sadly, by week's end, the original script often turns into mush.

During a lunch with the Fox Network's President, amendments to a particular show were discussed. Dubin noticed something amiss in the script and resisted the change.

“You need to change it,” insisted the President.

“It won't be funny,” Dubin countered.

“You have to do it.”

“Why?”

“Because, I own you,” the President explained.

Richard Dubin, a man who always speaks the truth, grabbed the President’s lapels and told him, “Yes, but I can kill you.”

Within an hour, no one in LA would return Dubin’s call. Over a lunch, he became persona non grata. (There was no email or text in this ancient era.) He left the city a few months later, returning occasionally for script doctoring gigs. Hardly a broken man, he would soon flourish for nearly two decades as the most popular Professor at The S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. Today, a gaggle of industry insiders, Syracuse graduates, readily acknowledge the important lessons Dubin taught in his classes.

Our friendship has endured for over half a century. In the early 70s, he was also a taxi driver and while I was in film school, I cast Dubin in his breakthrough film debut, as an outspoken tunnel digger in my film about taxi driving, “Rough Ride.”

This was great! Fellini-esque definitely in L.A. Those two tunnel diggers with their captive taxi driver are completely diabolical. "Ya gotta have peace of mind, man!" I love hearing about your "journey". Thanks for the posts.