It was November 2, 1975, when Pier Paolo Pasolini’s battered, burned, and brutalized body was found on the beaches of Ostia, Italy. It wasn’t just murder—it was a message, a modern crucifixion played out on the cinematic stage of real life. Run over multiple times, beaten with a metal rod, and set ablaze, Pasolini’s end read like the final act of one of his own controversial films. The truth of his demise? Wrapped in conspiracies, soaked in the blood of Italy’s political chaos, and overshadowed by the provocative ghost of his last film, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom.

Pasolini wasn’t just a filmmaker—he was a firebrand, a provocateur, and a poet of filth and beauty. This man stared into the abyss of fascism, consumerism, and the hypocrisies of modern life, and he saw hell looking back. Then he made a movie about it—a masterpiece so grotesque and relentless that it could very well have signed his death warrant. Buckle up, because this is where art, politics, and madness collide.

The Maestro’s Dark Symphony

Before diving into the carnage of Salò, you have to understand Pasolini’s world. Born in 1922 to a military family, his early years were a cocktail of small-town life and Italian traditions, spiced with the personal tragedy of losing his brother to war. Pasolini eventually moved to Rome, where the cultural decay of modernity hit him like a sucker punch. To him, capitalism wasn’t just an economic system—it was a monster, devouring the soul of Italy’s authentic traditions.

Pasolini’s films weren’t entertainment; they were provocations. He started with Accattone, a raw portrait of Roman slum life, and then made the Trilogy of Life—a celebration of sex and archaic traditions. But soon, his tone darkened. The world he saw was becoming an unholy union of fascist control and capitalist homogeny. The old Italy, with its beauty and innocence, was gone. What replaced it? A consumerist hellscape, where people were reduced to products and culture was processed like fast food. Cue Salò.

Welcome to Hell

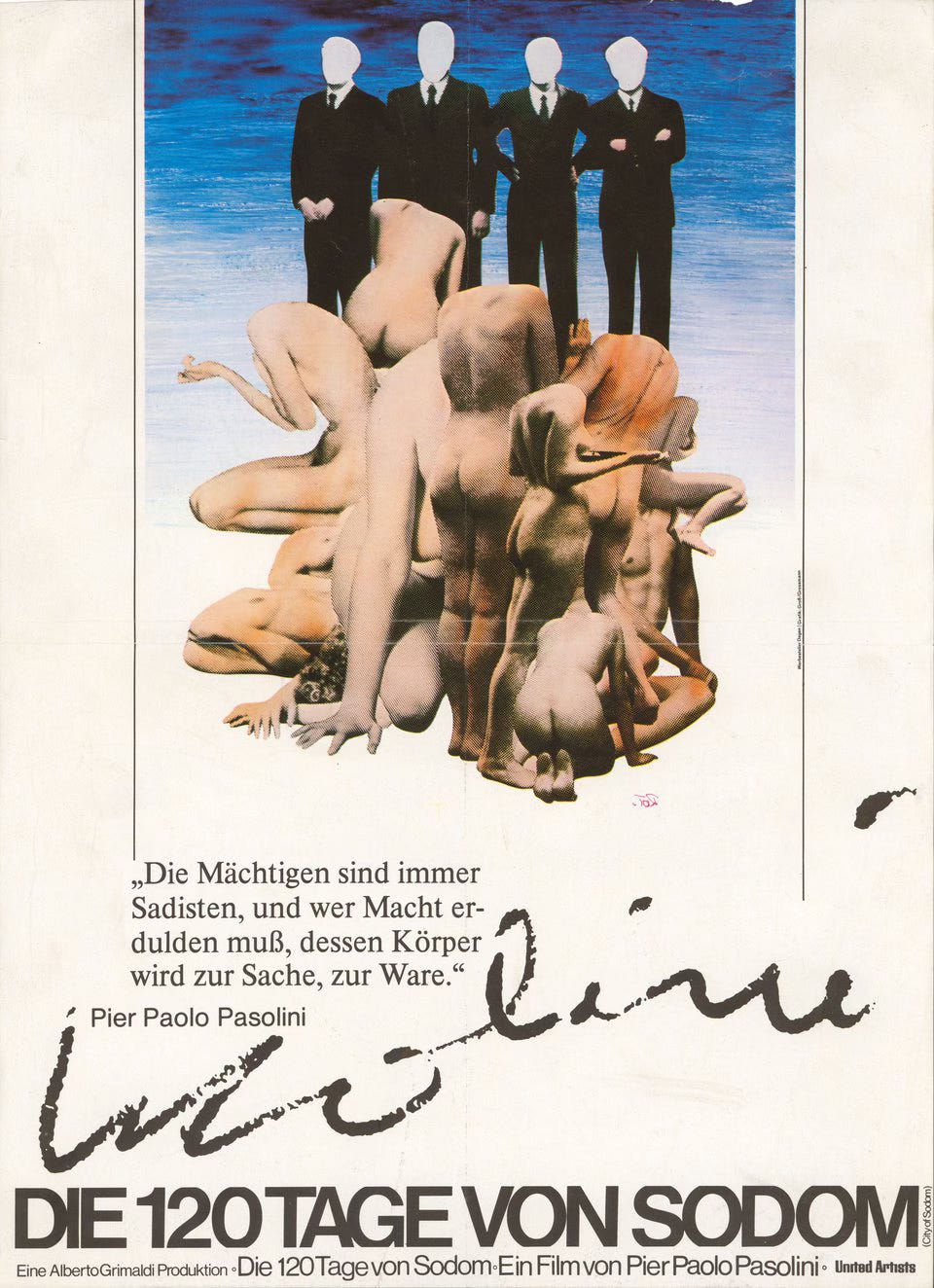

Salò wasn’t just a film—it was a dare. Based on the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom and set in Mussolini’s fascist puppet state, the film drags you through the inferno of power and depravity. Imagine four Libertines—representing the Church, Judiciary, Aristocracy, and State—sequestering a group of young captives in a mansion where rules and morality are shredded. Over the course of 120 days, they inflict every conceivable horror on their victims. Yes, it’s vile, but it’s vile with a purpose.

Pasolini didn’t just show atrocities for shock value; he painted a picture of power’s true face. The Libertines are impotent—literally and figuratively. Their only thrill comes from breaking taboos, escalating their depravity as each act loses its sting. This isn’t just about fascism—it’s about what happens when consumerism, power, and dehumanization collide. Pasolini turns the Libertines’ mansion into a microcosm of modern society, a place where fast food becomes literal excrement and human lives are reduced to disposable commodities.

And the rituals! Oh, the rituals. Each day begins with a grotesque tale told by one of the Libertines’ accomplices—a twisted mockery of storytelling, meant to prime the victims for the horrors ahead. Weddings become desecrations. Religion is banned under penalty of death. Pasolini’s point is clear: When power is absolute, it annihilates everything, even the sacred.

The Death Scene

Let’s be real—Pasolini’s own murder plays out like an Italian noir. A 17-year-old boy, Pino Pelosi, was caught driving the filmmaker’s car and quickly confessed to the murder. But his story didn’t add up. Pasolini was strong and trained in martial arts; Pelosi wasn’t. There were no signs of a struggle on Pelosi, and forensic evidence suggested multiple attackers. Decades later, Pelosi recanted, claiming neo-fascists had threatened his family if he didn’t take the fall.

The plot thickened. The film reels of Salò had been stolen shortly before Pasolini’s death. Witnesses emerged, pointing to political motives and high-ranking conspirators. Pasolini had been working on a book exposing government corruption, and many believed his murder was a silencing act. Was it fascists? The mob? Someone higher up? We still don’t know. What we do know is that his death was staged—a grotesque, public execution designed to send a message: Don’t mess with the status quo.

The Legacy of Defiance

Pasolini once said, “The saints, the hermits, the intellectuals, the ones who shaped history are the people who said no.” His life was a resounding “no” to everything he saw wrong in the world—consumerism, authoritarianism, the commodification of culture. His death didn’t silence him; it amplified his message. Salò remains one of the most debated films of all time—not for its grotesque imagery, but for its brutal honesty about power’s corrosive effects.

In the final scene of Salò, two guards dance to soft jazz while atrocities unfold behind them. It’s a chilling image, one that sums up Pasolini’s view of modern life: We’re all complicit, dancing to the tune of destruction, pretending not to see the horrors around us.

Pasolini’s story is a warning. The monsters aren’t in the shadows—they’re in the mirror. His death is still shrouded in mystery, but his message is crystal clear: Wake up, before the Libertines come for us all.

Pier Paolo Pasolini Speaks:

On Friday, join me for Albert Ayler and the Sound of Revolution. The late tenor saxophonist redefined jazz and divided the music world.

And next Monday, a subject close to my heart: Jewish Humor: A Legacy of Resilience, Adaptation, and Laughter.

Until then, let your conscience be your guide.

Nice read. 👍