Art Blakey stands as one of jazz’s most influential figures for several interconnected reasons that go far beyond his considerable abilities as a drummer. To understand his importance requires looking at both what he did behind the drum kit and what he accomplished in front of it as a bandleader, mentor, and guardian of the music’s future.

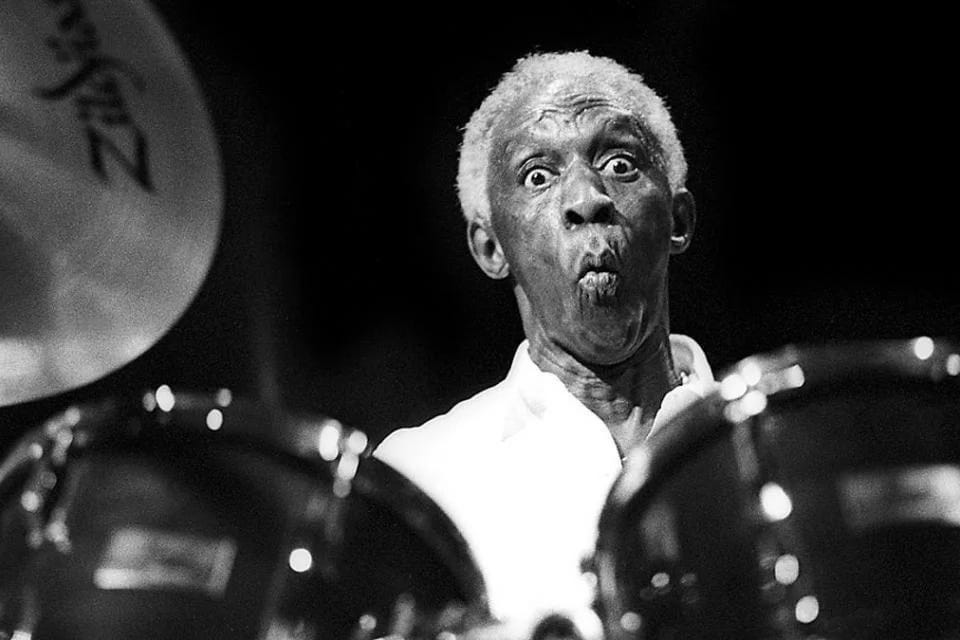

As a percussionist, Blakey was revolutionary. He brought an almost primal intensity to the drums, playing with a force and fire that could drive a band into ecstatic peaks. His press roll on the snare became his signature sound, this thunderous, tumbling cascade that announced his presence on every recording. Listen to “Moanin’” or “A Night in Tunisia” and you hear drums that don’t just accompany but command, that don’t merely support but inspire and provoke.

He didn’t just keep time; he created an emotional landscape. Where earlier drummers focused on smooth, even swing, Blakey brought African polyrhythms and a gospel-inflected power that made the drums a frontline instrument rather than mere accompaniment. He studied African and Caribbean rhythms, incorporating them into his playing in ways that connected jazz back to its deepest roots. When Blakey hit the drums, you felt it in your chest, in your gut. There was nothing polite or restrained about his approach. He played with the intensity of a preacher at revival, understanding that jazz was about ecstasy and transcendence as much as technical sophistication.

His touch was also remarkably varied. He could whisper on the brushes with extraordinary subtlety, then explode into polyrhythmic fury that pushed soloists to their absolute limits. Horn players who worked with him talk about how his drumming didn’t just support their solos but engaged in conversation with them, answering their phrases, challenging them, lifting them higher than they thought they could go.

But his drumming, however extraordinary, was almost secondary to his role as a bandleader and talent developer. The Jazz Messengers became the single most important proving ground for young jazz musicians from 1955 until his death in 1990. Think about that longevity and what it meant: for 35 years, Blakey was actively discovering, nurturing, and launching careers. No other bandleader in jazz history maintained that kind of commitment to youth development for so long.

The list of musicians who came through his band reads as a who’s who of jazz greatness: Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Lee Morgan, Bobby Timmons, Benny Golson, Curtis Fuller, Cedar Walton, Keith Jarrett, Chuck Mangione, Joanne Brackeen, Wynton Marsalis, Benny Green, Bobby Watson, Frank Mitchell, Branford Marsalis, Donald Harrison, Terence Blanchard, Wallace Roney, Javon Jackson, and dozens of others. Each of these artists developed their voice within the Messengers before going on to lead their own groups and shape the music’s future.

Blakey had an uncanny ear for raw talent and an equally remarkable ability to create an environment where young musicians could take risks, make mistakes, and grow. He gave them featured space, encouraged their compositions, and taught them not just how to play but how to present themselves professionally on stage and in the business. He understood that being a jazz musician meant more than just blowing your horn; it meant understanding how to dress, how to speak to an audience, how to handle club owners and record executives, how to survive on the road.

Former Messengers talk about him with a mixture of awe and affection. He could be tough, demanding perfection in rehearsals and on the bandstand. But he was also generous, paying his musicians well when he could, protecting them from the industry’s sharks, and genuinely caring about their futures. When a young musician was ready to leave and start their own group, Blakey encouraged it. He never tried to hold anyone back. The Messengers was explicitly designed as a training ground, not a permanent home.

His commitment to hard bop when the music was being pulled in other directions also mattered enormously. While others chased fusion or free jazz in the 1960s and 70s, Blakey maintained the connection to blues, gospel, and swing while still allowing for modern harmonic sophistication. He proved that tradition and innovation weren’t opposites. You could honor the past while pushing forward. The Messengers’ music was accessible without being simplistic, sophisticated without being cold or academic.

This philosophical stance became increasingly important as jazz struggled commercially in later decades. Blakey showed that you could maintain artistic integrity while still connecting with audiences. His bands packed clubs and sold records because the music had joy, fire, and soul alongside its technical brilliance.

What you had with Blakey was a rare combination: a great artist who was also a great teacher, a businessman who understood how to sustain a working band for decades, and a man genuinely invested in the future of the music beyond his own career. He created an institutional structure within jazz when the music desperately needed it. While formal jazz education programs were just beginning to emerge in universities, Blakey was running the real conservatory, the one that taught you what no classroom could.

That’s why calling the Messengers “the real Jazz university” isn’t hyperbole but simple truth. More jazz musicians received their essential education in Art Blakey’s band than in any academic program. They learned by doing, night after night, navigating the complexities of group improvisation, learning tunes, developing stage presence, and absorbing the deep wisdom that could only come from a master who had lived the life and survived its challenges.

Art Blakey died in 1990, but his legacy continues through every musician he touched and through their students and their students’ students. The family tree that springs from the Jazz Messengers essentially encompasses modern mainstream jazz. When you listen to contemporary straight-ahead jazz, you’re hearing echoes of what Blakey built, taught, and protected. He didn’t just play the drums brilliantly; he ensured that jazz itself would have a future. That’s the mark of true greatness.

I was lucky to hear Bu many times in person, from 1971 until he passed, with a number of Jazz Messengers configurations. One quick story. Sometime in the 80s, the band was playing at Sweet Basil and of course the music was top shelf. After the set, I approached and complimented him on the birth of his new son, when Bu was in his 70s. He looked me in the eye and with seriousness replied, “Ain’t science wonderful.”

One of my favorite Jazz Messenger groups was the 1958 edition featuring twenty year old Lee Morgan on trumpet, Benny Golson on tenor saxophone, Bobby Timmons on piano, Jymie Merrit on bass and Art Blakey on drums. From a concert in Belgium, they play Timmon’s jazz standard, “Moanin’.”

the most underrated man in jazz history

Was fortunate to see the band with the Marsalis brothers and Billy Pierce in the 80s, at Fat Tuesdays in NYC. Sat right up against the stage railing with the bells of their horns in my face. What a time to be alive!