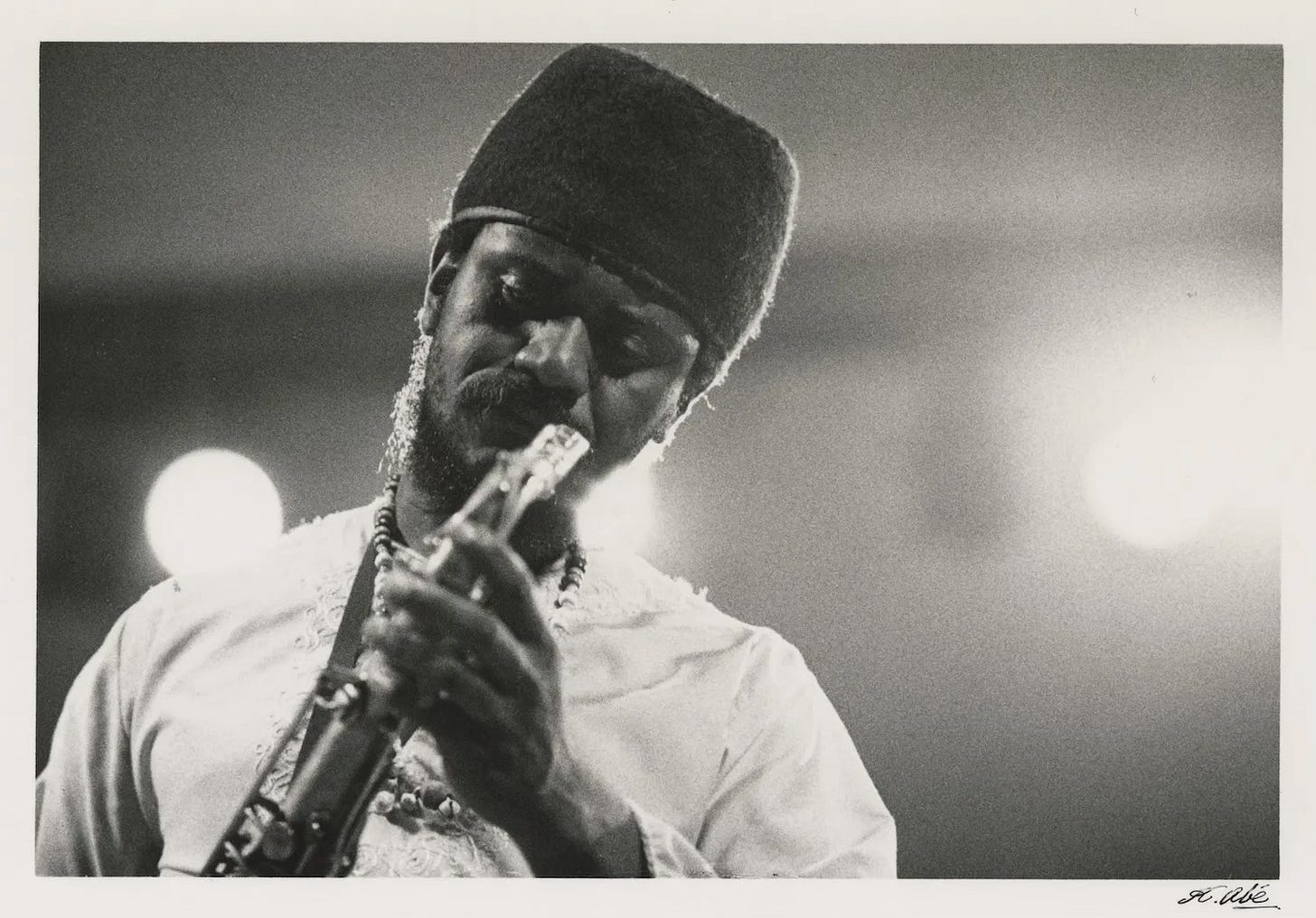

In the sweltering summer of 1971—four years after the death of John Coltrane—Pharoah Sanders walked onto the small stage at The East, a Black nationalist arts center in Brooklyn, and ignited the room with a scream that wasn’t just saxophone—it was survival.

The spirit of Coltrane had not faded. It had fractured, dispersed, and reincarnated inside the voice of Pharoah.

By 1971, Coltrane was myth. A martyr. A mountain that had collapsed into the sea, leaving behind an ocean of influence. But where many stood paralyzed in awe, Pharoah kept moving—not as a disciple frozen in reverence, but as a radical explorer carrying the torch into even stranger realms.

FROM THE SIDEMAN TO THE MESSENGER

Sanders joined Coltrane’s final band in 1965—when Trane’s music had already begun to split atoms. The sounds were dense, raw, terrifying to many. But Pharoah understood. He added overtones, screams, guttural howls, and sheets of energy to Coltrane’s already unearthly palette. Critics mocked it as noise. But to those listening with soul instead of skepticism, it was prophecy.

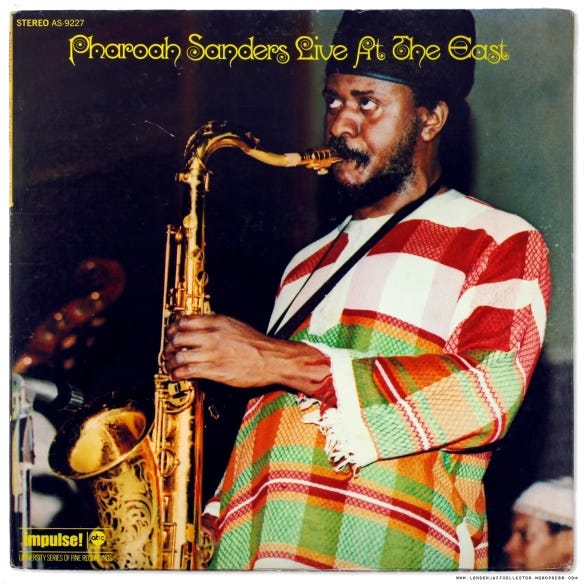

When Coltrane died in 1967, Pharoah didn’t retreat into traditionalism or safe gigs. Instead, he doubled down. Karma(1969) and Jewels of Thought (1969) sounded like interstellar radio broadcasts from a higher frequency. By 1971, with Live at the East, he had become something more than a saxophonist. He was a shaman.

THE EAST: SACRED GROUND FOR SACRED SOUND

Recorded on August 8, 1971, Live at the East captures Pharoah at a turning point. The venue—The East in Brooklyn—wasn’t a nightclub. It was a community temple, a space run by and for Black people, where art, politics, and spirituality fused.

The concert feels less like a performance and more like a ritual. The opening track, Healing Song, is a chant of rebirth—percussion layers building a bed for call-and-response horns and communal vocals. Memories of J.W. Coltrane is rawer: a spiritual seance powered by grief and groove. The band doesn’t imitate Trane—they conjure him. His presence hangs in the air like burning incense.

The personnel here was no mere backing band:

Joe Bonner’s piano was cosmic but rooted, channeling McCoy without mimicking him.

Cecil McBee’s bass—earthy, propulsive, deeply grounded.

Norman Connors and the percussion team (including Chief Bey) created a soundscape more akin to ceremony than jazz set.

And Pharoah? He doesn’t so much solo as wail prayers into being. His horn is a ritual object. A flame. A sword.

FOUR YEARS LATER: THE MESSAGE EVOLVES

By 1971, the jazz world had splintered. Fusion was rising. Miles Davis was deep into Bitches Brew territory. Free jazz was still ridiculed by many. But Pharoah wasn’t chasing trends or chasing ghosts. He was channeling energy, healing pain, and building sound temples for the soul.

Coltrane had left behind A Love Supreme, Ascension, Meditations. Sanders was now building on that foundation, not by repeating it, but by making it communal. Where Coltrane had often been solitary in his seeking, Pharoah built his records like villages—with vocal chants, layered percussion, flutes, and African rhythms.

1971 wasn’t just “post-Coltrane jazz.” It was a spiritual continuation through other frequencies. If Coltrane’s music was a vertical path—reaching higher and higher—Pharoah’s was horizontal, spreading outward, into community, ritual, earth, and ecstasy.

THE LEGACY: NOT AN ECHO, BUT AN EVOLUTION

Pharoah Sanders didn’t try to replace Coltrane. He honored him by evolving—by making healing the center of sound, by embracing repetition as meditation, and by using the horn as vessel for spirit, not ego.

And for those of us listening today, Live at the East isn’t just an archival gem. It’s a blueprint.

A guide for how to mourn without freezing.

A model for how to honor legacy without being imprisoned by it.

A reminder that sound can cleanse, provoke, heal, and lift us beyond language.

Because four years after Coltrane’s death, Pharoah didn’t just keep the fire burning.

He became the fire.

Listen to “Healing Song”

Pharoah Sanders - Tenor Saxophone

Harold Vick - Tenor Saxophone, Vocal

Carlos Garnett - Flute, Vocal

Hannibal Marvin Peterson - Trumpet

Joe Bonner - Piano, Harmonium

Cecil McBee - Bass

Stanley Clarke - Bass

Norman Connors - Drums

Billy Hart - Drums

Lawrence Killian - Congas, Balafon

Now, as Paul Harvey used to say, here’s the rest of the story.

Pharoah Sanders underwent one of the most dramatic stylistic transformations in jazz history. When he joined Coltrane’s group in 1965, he was indeed playing some of the most intense, abrasive free jazz being made. His tenor saxophone work on recordings such as “Ascension” and “Meditations” featured overblowing, multiphonics, and sheets of sound that pushed beyond even what Coltrane was doing. Sanders seemed to be searching for pure energy and spiritual transcendence through sheer sonic force.

After Coltrane’s death in 1967, Sanders began gradually softening his approach. By 1969’s “Karma,” he had found a middle ground between accessibility and spiritual exploration. The album’s centerpiece, “The Creator Has a Master Plan,” became his signature piece, blending his fierce tenor with Leon Thomas’s yodeling vocals over a hypnotic groove. This marked the beginning of what would become Sanders’ distinctive style: spiritual jazz that incorporated African rhythms, modal harmonies, and more melodic sensibilities.

Throughout the 1970s, Sanders moved further toward lyricism and beauty. Albums for Impulse! Records showed him embracing world music elements, particularly African and Eastern influences, while his tone became warmer and more vocalized. He developed his famous “sheets of beauty” approach, where cascading runs of notes would flow with an almost vocal quality. His ballad playing became particularly notable during this period, revealing a romantic side that was barely hinted at during his free jazz years.

The 1980s and beyond saw Sanders continuing to mellow, though he never completely abandoned his ability to unleash powerful, searching solos when the spirit moved him. His later work often featured him in more conventional jazz settings, playing standards and ballads with a gorgeously burnished tone. Yet he retained that spiritual searching quality that connected all phases of his career. Even in his most accessible moments, there was always that sense of reaching for something transcendent, just through gentler means than the volcanic eruptions of his youth with Coltrane.

I’ve heard Pharoah live a number of times, in different periods. One of his best groups, included John Hicks on piano, Walter Booker on bass and Idris Muhammed on drums, a world class rhythm without a doubt. Here’s an incredible 1981 live version of one of Pharoah’s most well known tunes, “You’ve Got to Have Freedom.” There aren’t enough superlatives to convey the level of musicianship and excitement on these fourteen minutes of jazz bliss that was released on Theresa Records in 1982.

I have a chapter in my book, How John Coltrane Changed Me, about the first time I heard Pharoah live, at the Village Vanguard in 1970. You can read it here, on my Coltrane site, Coltrane Code. The site is packed with Coltrane media including rare video and recordings.

Your book arrived on Monday and I'm about thirty pages into it. Great read. It's always interesting to see how music directly transforms people's lives. I've only seen Pharoah live once, at Catalina's about twenty years ago. William Henderson on piano, Alex Blake on bass, and the unexpected but worthy Ralph Penland on drums. I thought the stage would levitate from all that energy.

Grateful to have heard over 100 sets by the great Pharoah Sanders!!