The Man Who Called Coltrane “Anti-Jazz”

John Tynan, Jazz Critic, and the Firestorm That Followed

In November 1961, a jazz critic lit a match—and half the music world caught fire.

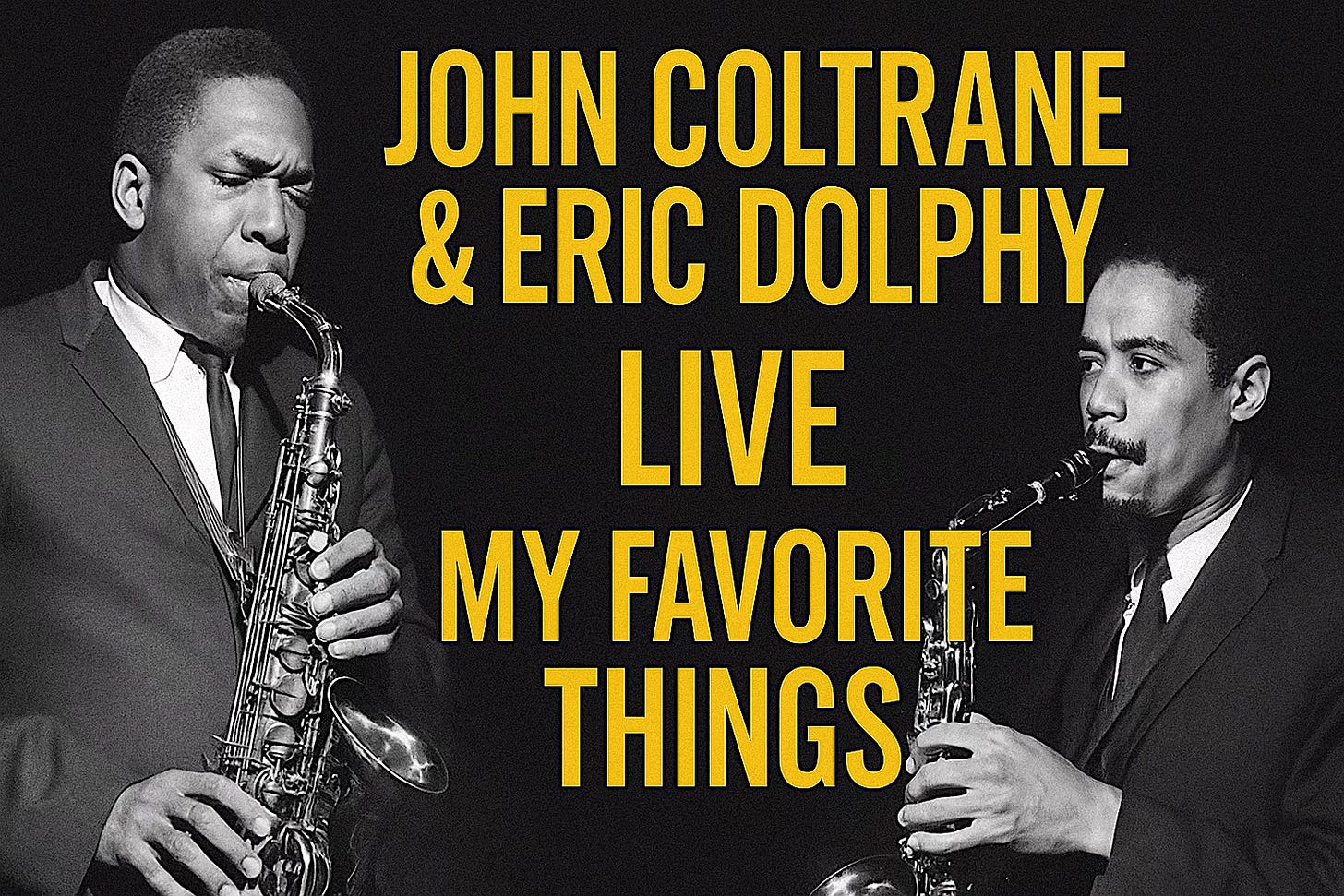

His name was John Tynan, a columnist for Down Beat magazine, then the most powerful voice in American jazz journalism. His target? Two saxophonists pushing sound past the known limits of melody and form: John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy.

After witnessing their performance at the Los Angeles Jazz Workshop, Tynan didn’t mince words. His review detonated with this now-infamous line:

“I heard a good rhythm section… go to waste behind the nihilistic exercises of the two horns. Coltrane and Dolphy seem bent on pursuing an anarchistic course… that can but be termed anti-jazz.”

“Anti-jazz.”

Let that sink in.

It wasn’t just criticism. It was a verdict. A declaration that what these men were doing onstage didn’t count as jazz at all.

To many, Coltrane and Dolphy were prophets. They weren’t just playing notes—they were channeling cosmic vibrations, fusing African spirituality, Eastern philosophy, and avant-garde experimentation into sound. Their performances were messy, beautiful, terrifying, ecstatic. And to some critics—like Tynan—they were heresy.

The response was volcanic.

Letters poured into Down Beat—from fans, musicians, even fellow critics—slamming Tynan’s take. The magazine, to its credit, published many of them. Coltrane and Dolphy responded in a now-historic interview, defending the freedom and emotion at the heart of their sound.

But make no mistake: Tynan’s review became a line in the sand.

On one side: the gatekeepers of jazz tradition.

On the other: a generation of seekers who believed the music was meant to evolve—or die trying.

Here’s the twist: Tynan wasn’t always allergic to the avant-garde. Just a few years earlier, in the 1958 Down Beat Critics Poll, he was the only writer to vote for Ornette Coleman, then a total unknown. He recognized something raw and honest in Ornette’s chaos. So what changed?

Maybe it wasn’t the chaos.

Maybe it was the spiritual fire behind it—the intensity, the refusal to make it palatable.

Or maybe Coltrane just scared him.

John Tynan died in 2018 at age 90. By then, the world had long embraced Coltrane as a saint of sound, and Dolphy as a martyr to modernism. Tynan, meanwhile, became a symbol—not of ignorance, but of the uneasy tension between tradition and transformation. Every jazz fan has to reckon with that tension eventually.

Tynan was wrong—but also necessary.

He gave the revolution a critic to push against.

And sometimes, a revolution needs just that.

So the next time you hear the sonic storm of Ascension, or the haunting weep of Dolphy’s bass clarinet on Out to Lunch, spare a thought for John Tynan.

He heard the future—and recoiled.

The rest of us leaned in.

Listen to John Coltrane and Eric Dolphy Live at Birdland, 1962. McCoy Tyner, piano, Jimmy Garrison, bass and Elvin Jones, drums. Symphony Sid Torin, announcer.

1 Introduction (Symphony Sid Torin) The Inchworm (F. Loesser)

2 Mr. P.C. (J. Coltrane)

3 My Favorite Things (R. Rodgers-O. Hammerstein)

Until we meet again, let your conscience be your guide.

Hi Bret. Worth noting that after this review appeared in DB, my friend Don DeMicheal (that is the correct spelling)—imo the best editor the magazine ever had—invited Coltrane and Dolphy to respond to Tynan and his ilk, which they did quite eloquently. Here’s the link:

https://downbeat.com/microsites/prestige/dolphy-interview.html

Philip Larkin, a renowned English poet, was known for his love of traditional jazz, particularly the styles popular before the 1940s. However, his views on avant-garde jazz were generally critical, reflecting a broader dislike for modernism in the arts.

In his collection of jazz writings, All What Jazz: A Record Diary, Larkin expressed his disdain for musicians like John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman, considering their work a departure from what he deemed "proper jazz".