The potential transformation of America's political landscape has sparked widespread speculation. In the near future, observers wonder if the United States might mirror authoritarian regimes, drawing parallels to historical or current examples of such governance. Will the U.S. in 2025 show similarities to North Korea under Kim's rule, or will it reflect aspects of Mussolini's Italy? Some consider a scenario akin to Orbán's Hungary, representing a less extreme shift. The unfolding political events of 2024 will reveal the direction of these changes.

In February 1986, I visited the People’s Republic of China, a country clearly in the throes of totalitarianism. At the time, Deng Xiaoping was the main man, best known for initiating the major economic reforms that led to significant economic growth and improved the standard of living for many Chinese citizens.

Deng Xiaoping's tenure, though marked by economic liberalization, was characterized by a strict control over political dissent, clearly demonstrated during the government's response to the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. These protests, largely spearheaded by students, demanded political reform and greater freedoms in speech, press, and government transparency.

A particularly distinctive aspect of these demonstrations was the live coverage by CNN and other American news outlets, broadcasting from Beijing. This exposure led to a rapid swell in participant numbers and sparked discussions globally about Chinese freedom, a topic not openly addressed in over a century.

Within a few weeks, the Chinese government cut off media access and violently suppressed the protests, resulting in the deaths of an unknown number of demonstrators. This brutal crackdown has since been largely erased from official Chinese history, rarely mentioned or acknowledged within China.

This act of censorship highlights the influence exerted by authoritarian governments. Although he introduced economic reforms, Deng Xiaoping, the successor to Chairman Mao, was a ruler who inflicted considerable hardship on this Asian country.

Why would we choose to travel to China, a country not typically seen as a tourist destination? The reason was deeply personal. My first wife, Meng, hailed from the People's Republic of China. She was among the pioneering group of students permitted to leave China for overseas studies in 1982. Our paths crossed and led to marriage, a unique tale in its own right. Meng came to the United States with her younger sister, Foo, also a student. However, her brother and parents remained in mainland China.

A year later, her mother passed away. Concerned about her father's health, Meng felt it was imperative to try and help her father escape. Securing an American visa for Chinese citizens during that period was a formidable challenge, but we resolved to make the journey to China. We were hoping a visit to the American consulate in Guangzhou might result in a visa for her father.

Guangzhou, once widely referred to as Canton, serves as the capital and the largest city of Guangdong Province in southern China. It's situated merely 75 miles from Hong Kong. Our arrival in the city coincided with the period just after the Chinese New Year in February 1986, when we encountered a chilly climate. At that time, coal was the primary source of heating, closely followed by cow dung. The reliance on these materials resulted in a pervasive, thick gray smog that blanketed the city.

After arriving in Guangzhou via Hong Kong, I immediately sensed a distinct change in atmosphere. Traveling often involves exploring new cities on foot, and as I wandered through Guangzhou's busy streets, I couldn't help but notice a pervasive sense of sadness, even despondency, among the people. This was almost a decade before the economic transformation that would bring a surge of tourists to the city.

My presence attracted attention, not just because I was Caucasian, but also due to my height. I was truly a giant among men. People would frequently stare at me in silence. Most of my interactions, apart from those with shopkeepers eager for American dollars and my ex-wife's family, were with locals keen to practice their English. These brief exchanges invariably ended with them asking if I could assist them in obtaining a visa. There was a palpable desperation to leave among many of the people I encountered.

Meng's father, Ping Luo, had a remarkable life, having been part of the Chairman Mao’s Long March, a pivotal moment in China's history. This event, from 1934 to 1936, involved the Red Army of the Communist Party of China embarking on a strenuous 9,000-kilometer retreat to elude the Kuomintang army. This demanding trek through China's demanding landscapes played a crucial role in molding the future of the Communist Party, reinforcing Mao Zedong's position as a leader and setting the stage for the Party's later triumphs.

After the birth of the People’s Republic, Mr. Luo relocated to Nanning, a smaller city in the South of China, just one hundred miles from the Vietnamese border. He became a high school principal and a Communist party official. His wife was a teacher at the school. After the birth of two girls and a boy, they experienced the nightmare of the Cultural Revolution, starting in 1966. Its aim was to preserve Chinese Communism by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society, and to re-impose Maoist thought as the dominant ideology. There were numerous attacks on cultural artifacts, and widespread persecution of intellectuals, party officials, and anyone seen as an enemy of the revolution.

Ping Luo endured public humiliation, marched through the streets with a wooden board around his neck labeled "capitalist roader." Meanwhile, his two daughters were relocated to a rural area, sent to live with farmers to experience a starkly different, decidedly non-capitalist way of life. In these basic, rural settings, they spent over two years away from their family, a separation aimed at ensuring they were not influenced by capitalist ideologies.

The Cultural Revolution effectively ended with the death of Mao. By October 1976, the "Gang of Four," a political faction that included Mao's wife Jiang Qing and had been closely associated with the most radical aspects of the Cultural Revolution, was arrested and later tried, signaling the end of the movement. That’s when Deng Xiaoping consolidated power and steered China away from the extreme policies of the cultural revolution. And when Ping Luo returned to his school.

He journeyed from Nanning to Guangzhou to meet us, and on our first full day in China, we dined at the home of a local Communist Party official. At that time, party officials held high societal status. The official's modest apartment, reminiscent of a housing project from the South Bronx, was located on the sixth floor of stone edifice with no elevators. While it had basic amenities the bathroom lacked standard plumbing fixtures, featuring only a hole in the floor with a stream of running water. The two bedrooms were adorned with calendars on every wall, similar to those often found in Chinese restaurants today.

Despite my familiarity with Chinese cuisine from my Jewish upbringing, I was initially surprised by the first dish served during my dinner in China. The soup presented was dark and had a strong odor. I considering declining the offering but not eating the soup would greatly offend my hosts. Somehow, I managed to consume half the bowl, hoping my effort would be seen as a gesture of goodwill and cultural appreciation.

To honor his American guests, our host intended to serve a special delicacy – a preserved turtle, typically reserved for unique occasions. Fortunately, I managed to politely decline by claiming to be a vegetarian. This small fabrication proved effective in avoiding that particular dish while maintaining respect for our host's hospitality.

Saving face, a key component of Chinese culture, refers to a complex concept centered around maintaining dignity, respect, and social standing both for oneself and others. It's deeply rooted in the values of honor, reputation, and social harmony. Consequently, it's uncommon for Chinese individuals to open up about themselves readily at first.

Throughout my journey, I was continuously struck by the country's stark, monotonous character. There was an oppressive feel to it, with its gloomy appearance and the pungent smoke that lingered in the air, making my two and a half weeks in China feel like punishment. While the culture, landscapes, and daily life were intriguing, the overall ambiance and spirit of the time in China had a somber tone. I couldn’t wait to get out of there.

Exploring a Chinese amusement park offered more intriguing glimpses into the country's culture at the time. Loudspeakers, a common feature everywhere we went, were playing a unique blend of Chinese rock music. In Cantonese, a local dialect, I heard a female singer covering Madonna's "Material Girl," creating an intriguing contrast with its capitalist themes in a communist setting. Additionally, food stalls around the park were selling barbecued dog. This, I realized, was likely a reflection of the country's history of overcoming periods of starvation, leading to a culinary tradition where a wide range of foods, including those less common in other cultures, are consumed. I passed on that.

Meng's family welcomed us with warmth and friendliness. Her ninth aunt made a two-and-a-half-hour journey just to bring us soup, a gesture that was deeply touching. Additionally, a group of students traveled for three hours to discuss the advent of personal computers in America.

Understanding the scarcity of consumer products at that time, we had brought along two suitcases filled with soap, shampoo, conditioner, cologne, and toothpaste, items that were received with great appreciation by Meng's family.

Despite our efforts, we couldn't convince the American consulate to issue a visa for Meng’s father, a result that was sadly expected. The Reagan administration held a strong anti-communist stance. American officials in Guangzhou appeared detached, showing little sensitivity to emotional appeals, including the compelling need to reunite a family that had experienced considerable hardship.

Several days later, following a train journey through a region that would eventually host numerous factories manufacturing Apple products, we crossed into Hong Kong. The contrast was striking; the ambiance, the energy felt significantly more positive, embodying the essence of a true democracy. I thoroughly enjoyed the week spent in Hong Kong, which was still under British rule in 1986.

China regained control over Hong Kong eleven years later, and in recent years there has been a noticeable decline in freedoms, including speech and press, introducing elements of repression to what was once a peaceful and open society.

The individual behind these significant alterations is Xi Jinping, who has an admirer in Donald Trump, for his strong arm tactics.

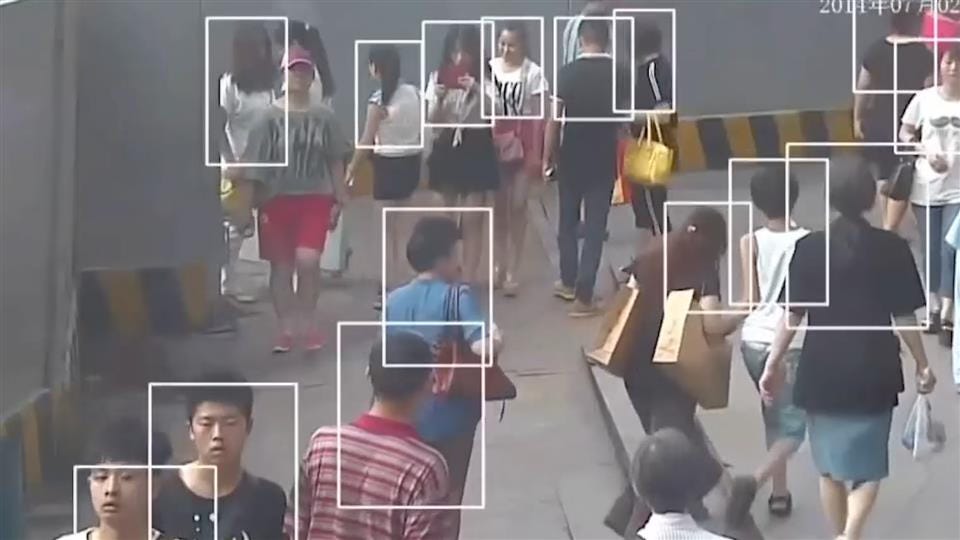

Life in China today as a surveillance state is characterized by a high level of government oversight and the use of advanced technology for monitoring and controlling the population.

China has one of the world's most sophisticated surveillance systems, including a vast network of CCTV cameras equipped with facial recognition technology. These systems are used for a variety of purposes, from traffic management to monitoring public behavior and dissent.

The government has developed a social credit system, which assigns ratings to citizens based on their behavior, financial creditworthiness, and other personal data. This system can impact people's access to services, employment, and travel.

The Chinese government exercises strict control over the internet through the "Great Firewall of China", which blocks access to many foreign websites and censors online content including Facebook and YouTube. Domestic social media platforms are closely monitored, and content deemed politically sensitive is quickly removed.

For many Chinese citizens, the high level of surveillance and control is a normal part of life. While it provides certain benefits like safety and order, it also restricts freedom of expression and privacy. People are often cautious about what they say and do, especially regarding political or sensitive topics.

To further control the population, the Chinese government relies on ordinary citizens informing on their neighbors, a complex and multifaceted phenomenon. This practice manifests in various forms ranging from community monitoring to digital surveillance. While some residents engage in these activities as a means of adhering to community norms or government directives, others may be motivated by personal incentives or a sense of civic duty. The integration of advanced technology and social media platforms has further facilitated this trend, allowing for more efficient and widespread monitoring.

In the United States, rapid advancement in AI and robotics does open possibilities for future scenarios that might have seemed far-fetched in the past. These changes depend on a mix of technology, politics, public opinion, and laws.

There is certainly no shortage of apocalyptic prophecy. I prefer being grateful for my life, and living in the present moment amidst these evolving factors. By focusing on the here and now, I can better navigate and appreciate the impact of these complex interactions. 2024 will be a year to remember.

From Richard. a belgian drummer in Vietnam,

Thank you Brett for this very interesting post.

I live 90 % of the time in Vietnam since 5 years and totally confirm what Barry says but on Vietnam.

I live in Hué, a 400000 inhabitants city with 40000 students in colleges.

I share your conclusions on the US as well as on Belgium or France.

It is very noticeable that the authorities are installing all the necessary devices

To control and reduce people's rights in every domain. ORWEL's 1984 is coming.

I lived in California for 7 years and miss

my american friends very much. But I wouldn't go back considering what I see happening in San Francisco for instance. This is also valid for Paris.

I ain't smart enough and I'm too old to figure out a solution to 50 years of crap TV manipulation and catastrophic decrease of morality in politicians mind.

With regrets, I give up the fight, play Jazz music, enjoy the life with my vietnamese friends.

To the young people I say: "I'm sorry for the mess you're in" .

Good luck to all of us. and without any irony , very best whishes for 2024 to everyone.

I'll go listen to Brecker/Ogerman's Cityscape : I need some beauty to focus on!

Richard

Fascinating post! Clearly the USA is already on its way to fascism!