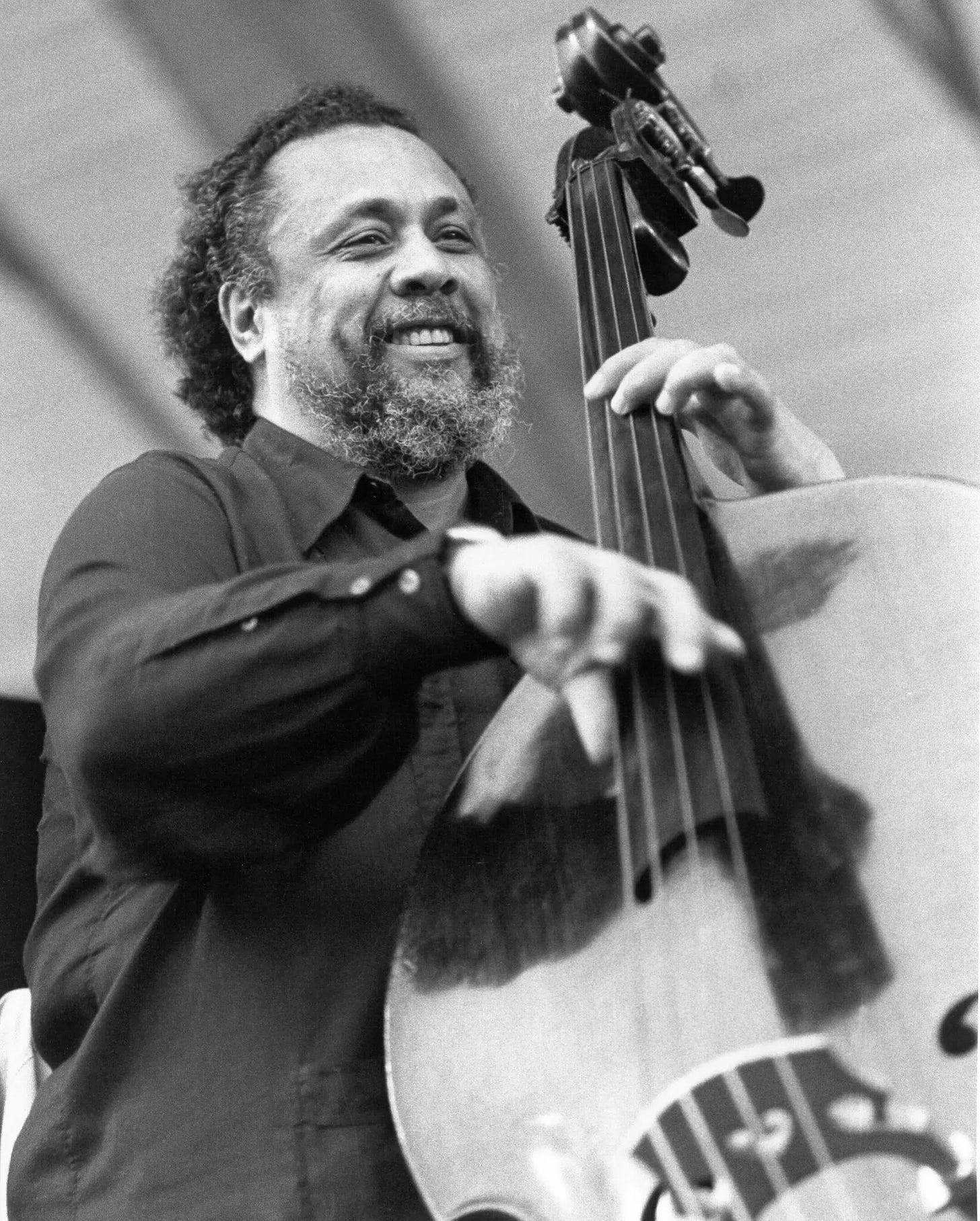

Charles Mingus was jazz’s great contrarian, a bassist who refused to stay in the background, a composer who wouldn’t color inside the lines, and a bandleader who treated his ensembles as extensions of his volcanic personality. More than four decades after his death, his music still sounds urgent, necessary, and absolutely uncompromising.

My first real encounter with Mingus came through “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat,” his elegy for Lester Young. I’d heard plenty of jazz ballads before, but this one carried a weight that went beyond melody and harmony. It was mourning made manifest, a sonic cathedral built from bass lines and saxophone cries. That composition taught me that jazz could be architecture, that a song could be a monument.

But Mingus was never just about the pretty stuff. He could write music that punched you in the gut, that made you uncomfortable, that forced you to pay attention. “Fables of Faubus” remains one of the most effective political statements in jazz history, its mockery of Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus sharper than any editorial. The way Mingus structured that piece, with its call-and-response vocals and its barely controlled chaos, showed me that jazz could be journalism, protest, and art simultaneously.

What really distinguishes Mingus from his contemporaries was his refusal to separate his music from his life. When you listen to “The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady,” you’re not just hearing compositions; you’re hearing confessions, arguments, love letters, and manifestos. He subtitled it “a jazz ballet,” but it plays more as psychodrama, with each movement revealing different facets of a deeply complex personality.

His approach to the bass transformed how I think about rhythm sections. Mingus didn’t just keep time; he drove the music forward, commented on it, argued with it. Listen to him on “Haitian Fight Song” and you hear the bass as protagonist, not accompanist. He played with a physicality that made you aware of the instrument’s size and power, those thick strings vibrating with an almost human voice.

The volatility that marked his personality also fueled his greatest music. His bands were workshops, laboratories, combat zones. He’d stop performances mid-song to berate musicians who weren’t meeting his standards, yet he could also nurture young talent with remarkable generosity. Eric Dolphy, Ted Curson, Dannie Richmond, Jimmy Knepper, and so many others found their voices in Mingus’s demanding but fertile musical environment.

What speaks to me most about Mingus now, particularly as I work on my Coltrane project, is how he embodied the full spectrum of Black American experience in his music. He could be tender and brutal, sophisticated and raw, deeply spiritual and earthily profane. His autobiography, Beneath the Underdog, reads as a companion piece to his music, equally unfiltered and uncompromising.

His extended works deserve more attention than they often receive. “Cumbia & Jazz Fusion” showed him exploring Latin rhythms with the same intensity he brought to the blues. “Let My Children Hear Music” found him working with larger ensembles, proving he could orchestrate for full orchestra with the same originality he brought to small combos. These weren’t experiments; they were expansions of an already vast musical vision.

The collaborative spirit of his Jazz Workshop groups set a template that still influences jazz education and performance. He wanted musicians who could compose on their feet, who understood that improvisation meant more than running scales over chord changes. When you hear those Workshop recordings, you’re hearing democracy in action, albeit a democracy with a very strong executive branch.

Living in Mexico now, I think often about Mingus’s relationship with Joni Mitchell, how she captured his essence in her album named after him. She understood that his anger came from love, that his demands for excellence came from respect for the music and its history. That’s the paradox of Mingus: the man who could be impossibly difficult was also impossibly generous with his art.

His influence extends far beyond jazz. You can hear his spirit in punk rock’s confrontational stance, in hip-hop’s autobiographical urgency, in any music that refuses to separate the personal from the political. He showed us that authenticity matters more than perfection, that honest mistakes beat dishonest precision every time.

As I continue my own journey through jazz history, documenting and analyzing this music that has shaped my life, Mingus remains a north star. Not because he was perfect, but because he was complete. He brought all of himself to his music, the beauty and the rage, the tenderness and the fury. In an age of careful brand management and calculated personas, his rawness feels revolutionary.

That’s why I will always love Charles Mingus. He proved that jazz could contain multitudes, that a bass could roar as loud as any horn, and that the only real crime in art is playing it safe. Every time I hear that opening bass figure from “Better Git It in Your Soul,” I’m reminded that music can be celebration and challenge simultaneously, that joy and struggle aren’t opposites but partners in the dance of creation.

Listen to “Cumbia and Jazz Fusion”

March 10, 1977, New York City.

Charles Mingus assembled a large ensemble with Latin percussion and jazz soloists for this piece. Musicians included:

Charles Mingus – bass, vocals, percussion, arranger

Jack Walrath – trumpet, percussion

Jimmy Knepper – trombone, bass trombone

Mauricio Smith – flute, piccolo, soprano saxophone, alto saxophone

Paul Jeffrey – oboe, tenor saxophone

Gene Scholtens – bassoon

Gary Anderson – contrabass clarinet, bass clarinet

Ricky Ford – tenor saxophone, percussion

Bob Neloms – piano

Dannie Richmond – drums

Candido – congas

Daniel Gonzales – congas

Ray Mantilla – congas

Alfredo Ramirez – congas

Bradley Cunningham – percussion

Thanks Bret, for a beautiful appreciation of this maestro. “Cumbia and Jazz Fusion” is the morning lift I didn't know I needed. Love the sounds of nature opening.

One late afternoon, Lili (my twin sister) and I were walking down Bleeker Street in the Village after a rehearsal. We were approached by a man who said to us " I have two tickets to see Mingus at Top of the Gate - would you two like them> I can't use them". Of course, we said yes. We climbed the stairs to the club, and the first thing that caught my attention, besides the music, was that the entire front section of the club had empty tables. Everyone attending was sitting further back. I didn't understand why - neither did Lili. As we began to maneuver where to sit, a waiter approached us and said "don't sit too close to the front." Well, we sat where we wanted to , which was to the side near the front with a great view of the band and Mingus himself. The show was great. As we left, Lili asked one of the other attendees why no one sat in the front. He replied "Mingus has been known to throw things!" That night, all he was "throwing" was amazing music. As always, thanks for this. Barbara