Excerpt from “John Coltrane’s Spiritual Odyssey Through Jazz - A Multimedia Biography” coming September 23rd on Amazon.

The Five Spot Laboratory

Essentially reborn after going cold turkey in Philly after getting fired by Miles Davis, John Coltrane returned to New York in mid-1957, and stepped directly into one of jazz history's most significant apprenticeships: a six-month residency at the Five Spot Café with Thelonious Monk. The booking was both opportunity and trial by fire—five nights a week, two sets a night, working through Monk's notoriously difficult compositions with one of jazz's most uncompromising musical minds.

The Five Spot was cramped and smoky, its piano positioned so close to the small bandstand that Monk and Coltrane could almost touch. There were no charts, no safety nets, just Monk's angular compositions and his cryptic guidance. Shadow Wilson on drums and Ahmed Abdul-Malik on bass completed the quartet, but the real conversation was between piano and saxophone.

Through the smoky corridors of the Five Spot, past tables crowded with hipsters and bebop disciples, beyond the cramped dressing rooms where legends changed clothes between sets, Coltrane discovered his true calling.

Monk's teaching method defied conventional pedagogy. He would play a composition once, maybe twice, then expect Coltrane to find his way through harmonic labyrinths that seemed to defy musical logic. Compositions such as "'Round Midnight," "Ruby, My Dear," and "Epistrophy" presented chord progressions that moved in unexpected directions, demanding improvisational approaches that went far beyond standard bebop vocabulary.

Monk didn’t just write songs—he deconstructed them, reassembling melody the way a cubist reimagines a face. Angular, cryptic, full of trap doors. You didn’t just play his music—you deciphered it.

"Monk's music was a puzzle," Coltrane later explained. "Every time you thought you understood it, he'd show you another layer." Night after night, Coltrane learned to think in new harmonic dimensions. Where other musicians heard individual chords, Monk taught him to perceive entire architectural structures—how chord progressions could create emotional narratives, how harmonic ambiguity could generate creative tension.

The most famous of these lessons involved Monk's composition "Trinkle Tinkle," a deceptively simple melody built over chord changes that shifted direction every few measures. Monk would stop mid-performance, letting silence hang in the smoky air, forcing Coltrane to navigate the harmonic maze alone. These moments of musical abandonment taught Coltrane self-reliance and deepened his understanding of how melody and harmony could interact in unexpected ways.

Between sets, Coltrane would scribble furiously in a notebook, mapping out Monk's harmonic logic as though decoding an ancient, sacred manuscript. He began to understand that Monk's seemingly random chord substitutions followed internal rules that prioritized emotional expression over conventional harmonic function. This insight would later inform his own compositional approach and his revolutionary reharmonization of standard songs.

“It was like studying a university course in music,” Trane later said. Monk was the professor. The bandstand, the blackboard.

Technical Revolution

The Monk experience catalyzed a technical revolution in Coltrane's playing that went far beyond the "sheets of sound" approach he'd developed with Miles. Coltrane didn’t just come out stronger. He came out changed—musically, spiritually, anatomically. He rewired the horn.

Multiphonics, altissimo, flurries of 16th notes—he pushed past what the instrument was built to do.

His practice routine, already obsessive, became almost monastic in its intensity. He would spend hours working on single scales, exploring every possible fingering and embouchure variation until he could execute complex passages at any tempo with complete control.

He devoured Slonimsky’s “Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns,” a book most musicians barely open. Trane didn’t just read it—he treated it not as music, but as a coded message from the divine.. None of it was about flash. Technique was the chisel. Spirit was the sculpture.

His vegetarianism, exploration of various spiritual traditions, and rigorous practice schedule during this period suggested someone who had discovered how to transform his obsessive tendencies into spiritual discipline. The same intensity that had nearly destroyed him through addiction was now serving his recovery and artistic development.

But technique served musical vision rather than mere display. The cascades of notes that had characterized his work with Miles now gained architectural coherence. Each phrase connected to larger harmonic structures, and his improvisations began to suggest multiple melodic lines occurring simultaneously. Critics noted that Coltrane seemed to be developing a new saxophone vocabulary, one that pushed the instrument beyond its traditional role as a single-line melodic voice.

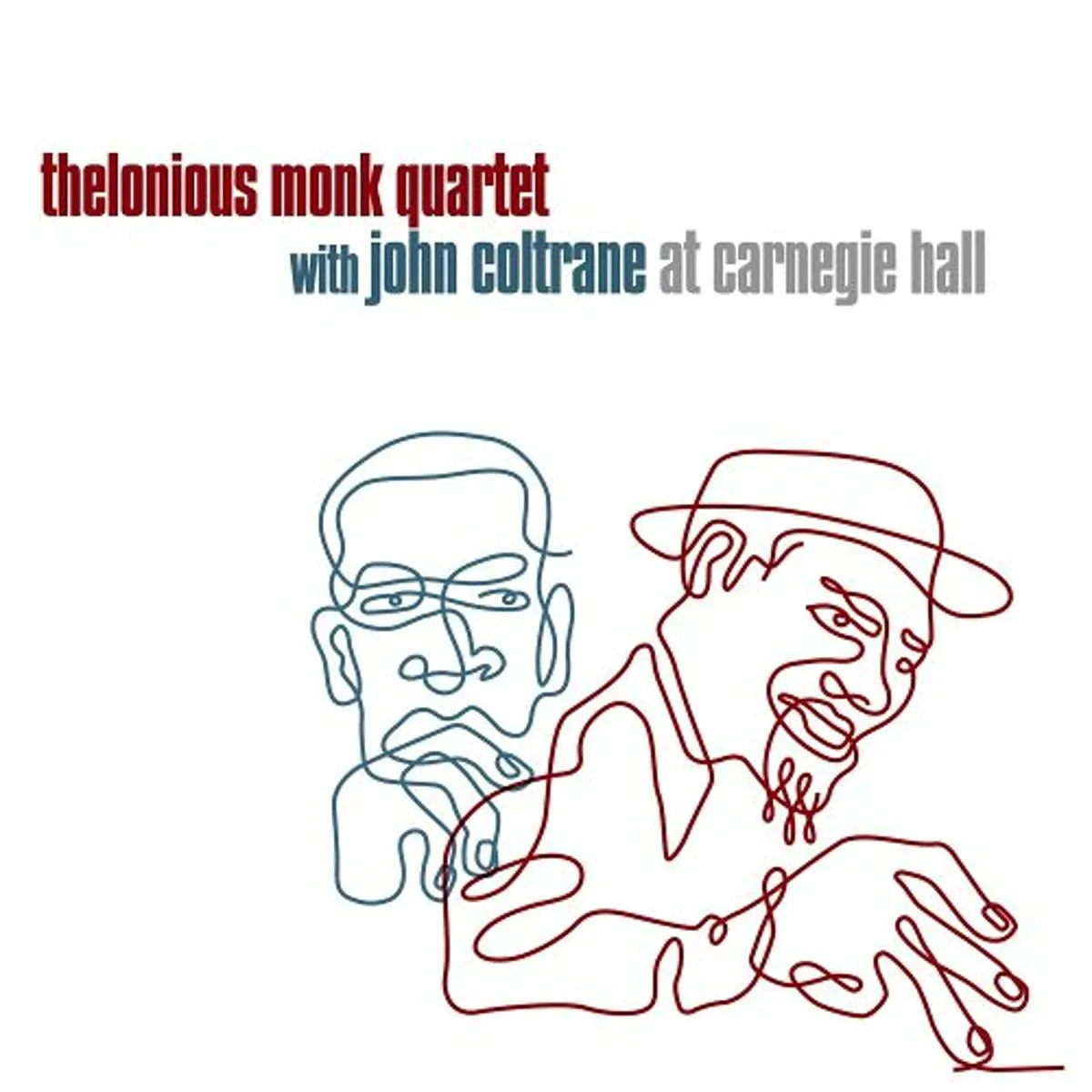

Most of it’s gone—vanished into memory and cigarette smoke. But the scraps that remain show Trane in metamorphosis. Monk and Coltrane Live at Carnegie Hall surfaced a few years ago thanks to the late Larry Applebaum of the Library of Congress.

The Significance of the November 29, 1957 Carnegie Hall Concert

The Live at Carnegie Hall recording from November 29, 1957, captures one of the most pivotal moments in John Coltrane's artistic development. This Thanksgiving weekend benefit concert for the Morningside Community Center documented the culmination of Coltrane's intensive apprenticeship with Thelonious Monk during their legendary residency at the Five Spot Café. The performance took place just months after Coltrane's spiritual awakening and recovery from heroin addiction, making it a crucial document of his transformation from struggling sideman to emerging master.

Their Performance of "Epistrophy" and "Blue Monk"

On Monk's composition "Epistrophy," Coltrane demonstrates his complete mastery of the composer's characteristically unpredictable harmonic language. His solo navigates Monk's angular chord progressions with newfound confidence, revealing how thoroughly he had internalized the pianist's approach to rhythm and harmony. The "sheets of sound" technique that defined his style with Miles Davis was already emerging, but here it remains disciplined by Monk's structural demands and sense of space.

"Blue Monk" provides perhaps the most revealing glimpse into Coltrane's artistic evolution. His interpretation shows how completely he had absorbed Monk's fundamental lesson: that harmonic complexity must serve emotional expression rather than obscure it. Each phrase of Coltrane's solo builds logically from the previous one while maintaining the bluesy essence that Monk never abandoned, no matter how abstract his harmonic innovations became. The performance demonstrates Coltrane's ability to balance technical sophistication with emotional directness—a skill that would become central to his later masterpieces.

Coltrane's Transformation from Student to Peer

The Carnegie Hall performance reveals a fundamental shift in the musical relationship between Monk and Coltrane. Rather than the teacher-student dynamic that had characterized their early collaborations, the recording captures two master musicians engaged in genuine dialogue. Coltrane's responses to Monk's harmonic provocations show complete confidence and independence, while still honoring the older musician's compositional vision. The interplay between piano and saxophone demonstrates the telepathic communication they had developed through months of nightly performances, but now with Coltrane as an equal partner rather than an apprentice.

The Concert's Role as a Bridge Between Apprentice Years and Mastery

Live at Carnegie Hall stands as the crucial bridge between Coltrane's formative period and his emergence as one of jazz's most revolutionary voices. Within months of this performance, he would record Blue Train—his first fully mature statement as a leader—and rejoin Miles Davis with a completely transformed musical personality. The Carnegie Hall recording preserves the exact moment when Monk's cryptic guidance had catalyzed Coltrane's evolution, showing how the harmonic and rhythmic concepts he learned during their collaboration would inform all his future innovations. The concert documents not just a performance, but a graduation—the completion of one of jazz education's most intensive and transformative apprenticeships.

Listen to Monk and Coltrane at Carnegie Hall

_ _ _ _ _

And until we meet again, let your conscience be your guide.

Monk’s music often sounds like something played by a brilliant and very strong six year old. The melodies are deceptively simple, yet full of tricks and quirks. Some Monk tunes evoke the sensation of almost stumbling over a crack in the sidewalk, then recovering without falling on your face. Monk is devious. He writes to test other musicians, to see if they can cut it, to separate the gold from the lead. The compositions are not so much difficult as subtle. It’s easy to hum a Monk tune, easy to let one of his lines slip into the rhythm of driving or shopping. His songs are like nursery rhymes made up by a man who is both autistic savant and cosmic seer. Monk seemed to live in several worlds simultaneously. The only location where all the worlds converged was in the piano . Monk’s music was so unconventional as to require use of elbows, forearms, crazed crushes of fingers. His right leg flopped like a hooked sturgeon when he played. He was famous for getting up and dancing a little jig while his sidemen solved the labyrinth of his chords. Were it not for the staggering originality of Monk’s ideas, he would never have been recognized, never acquired fans. He was barely functional and spent time in mental wards. Without his wife Nellie’s patient devotion, no one would know the name Thelonious Monk. It would be “What-lonius who?”

Whao! Professor, truly amazing. A little question, please. I wonder if you might know if the sound itself from these two artists…not even sure of the question. Maybe: is the sound from their instruments unique, or at least more developed or purer or something like that? Thank you.