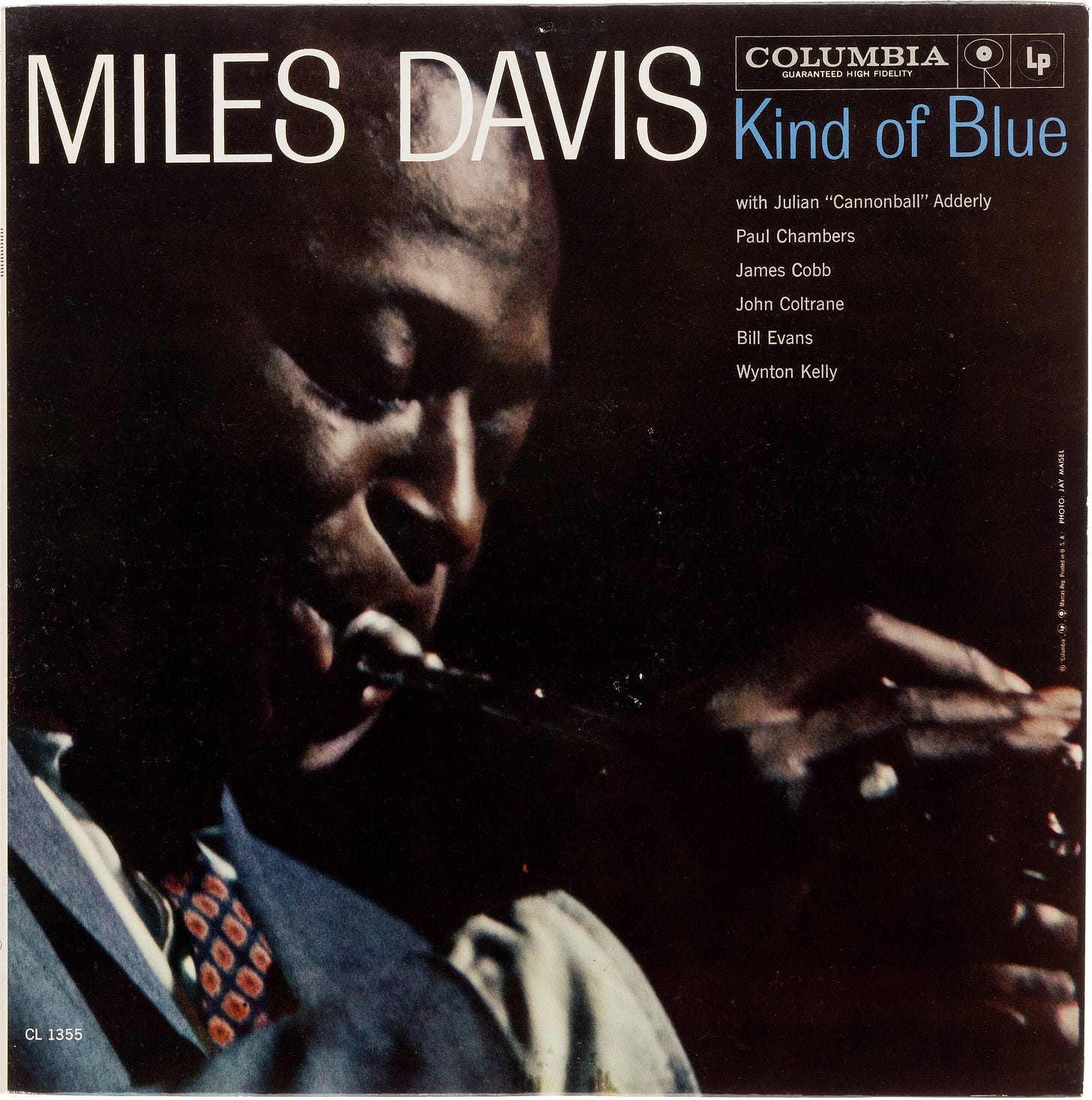

Miles Davis's Kind of Blue, recorded in 1959 and released on August 17 of that year, sixty six years ago last week, stands as one of the most significant achievements in the history of recorded music. More than half a century after its creation, this album continues to be regarded by critics and musicians alike as both a masterpiece of jazz artistry and one of the most influential albums ever recorded. Through its revolutionary approach to improvisation, its assembled talent, and its enduring cultural impact, Kind of Blue represents a watershed moment that fundamentally altered the trajectory of jazz music.

The year 1959 proved pivotal in jazz history, with multiple groundbreaking albums reshaping the musical landscape. The music was changing rapidly and drastically with albums like Ornette Coleman's The Shape of Jazz to Come, Charles Mingus's Mingus Ah Um, and Dave Brubeck's Time Out all released that same year. These recordings represented four dramatically different statements about how to organize jazz music, each avant-garde in its own way.

In this context of innovation, Miles sought to break free from what he perceived as the increasingly formulaic nature of bebop. Davis was definitely of the mind that the music had become a little paint-by-numbers, and he wanted to force the soloists to really reach inside themselves to come up with a much more individual expression. This desire for artistic renewal would drive Davis toward an entirely new approach to jazz composition and improvisation.

The musical foundation of Kind of Blue rests on the concept of modal jazz, a departure from the chord-change-based improvisations that dominated bebop. This approach drew inspiration from George Russell's Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization, published in 1953, which offered an alternative to improvisation based on chords and introduced the idea of chord/scale unity.

Miles himself explained this revolutionary approach, noting that when you go this way, you can go on forever. You don't have to worry about changes, and you can do more with time. It becomes a challenge to see how melodically inventive you are. He believed a movement in jazz was beginning, away from the conventional string of chords and a return to emphasis on melodic rather than harmonic variations.

The implications of this shift were profound. Rather than navigating through a complex series of chord changes that dictated harmonic movement, musicians were given scales or modes that provided a framework for extended improvisation. This approach offered fewer chords but infinite possibilities as to what to do with them.

Central to the album's success was the extraordinary sextet Davis assembled for the recording sessions. The ensemble featured saxophonists John Coltrane and Julian "Cannonball" Adderley, pianist Bill Evans (with Wynton Kelly replacing Evans on "Freddie Freeloader"), bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Jimmy Cobb. This was an all-star sextet Miles had assembled to accompany him, including three players (John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Cannonball Adderley) who would themselves prove to be jazz legends, and a rhythm section (Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers, Jimmy Cobb) that outswung any other in its day.

The role of Bill Evans proved particularly crucial to the album's conception and execution. Evans, who had studied with George Russell and understood modal concepts, was specifically recruited back into Davis's group for this project. His contribution extended beyond performance to the conceptual framework of the album itself.

The recording of Kind of Blue took place in just two sessions at Columbia's 30th Street Studio in New York City—March 2 and April 22, 1959. What made these sessions remarkable was Davis's commitment to capturing first takes and spontaneous creation. Davis believed that if you put a musician in a place where he has to do something different from what he does all the time, that's where great art and music happens.

The musicians arrived at the studio with only skeletal compositional sketches, forcing them to create in real time. This approach resulted in the shared feeling of fresh discovery in the studio on those two days in 1959, as almost all the tracks were the first complete takes—no edits, no second tries. Bill Evans captured this philosophy in his evocative liner notes, highlighting the concept of "first-mind, best-mind" and comparing their music-making to the spontaneous artistry of Japanese calligraphy.

From its release, Kind of Blue has been universally acclaimed by critics and historians. Music writers have described it as the distillation of Davis's art, while drummer Jimmy Cobb declared that the album must have been made in heaven. The album's significance extends far beyond critical praise—it has achieved the rare distinction of being both an artistic masterpiece and a commercial success, becoming the best-selling jazz album of all time.

The album's influence transcended jazz boundaries, affecting musicians across genres. Guitarist Duane Allman of the Allman Brothers Band acknowledged its impact, stating that his soloing comes from Miles and Coltrane, and particularly Kind of Blue. He had listened to that album so many times that for the past couple of years, he hadn't hardly listened to anything else. Pink Floyd's Richard Wright similarly credited the album's chord progressions with influencing the structure of the introductory chords to the song "Breathe" on the album The Dark Side of the Moon.

The album's historical significance has been formally recognized by major cultural institutions. In 2002, Kind of Blue was selected by the Library of Congress for inclusion in the inaugural National Recording Registry, being deemed culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant. Rolling Stone magazine has consistently ranked it among the greatest albums of all time, placing it at number 12 on their "500 Greatest Albums" list in 2003, though it was repositioned to number 31 in their 2020 revision.

Music scholars have argued that the album's cultural impact reflects broader social currents of its era, suggesting that Davis thus authoritatively married the blues to the freer forms of the musical avant garde in a manner reflecting the integrationist spirit of the racial politics of the era. This interpretation positions Kind of Blue not merely as a musical innovation but as a reflection of the complex social dynamics of late 1950s America.

Ironically, Davis himself viewed Kind of Blue with characteristic ambivalence. He described it as a failed experiment in his autobiography, explaining that the album did not fully realize the sounds he had been hearing in his head before the session. However, when confronted in 1986 with the observation that Kind of Blue was considered the number one jazz record on virtually all critics' lists, his sincere answer was short but held a palpable sense of pride: "Isn't that something."

This paradox reflects Davis's perpetual forward motion as an artist. The album represents just a snapshot into what Miles was thinking about in 1959, which in the case of an artist who was always on the move, was the equivalent of a still from a film reel.

Kind of Blue endures as a masterwork that successfully bridged artistic innovation with popular appeal. Miles Davis's 1959 recording Kind of Blue is indubitably a classic. It presents music making of the highest order, and it has influenced — and continues to influence — jazz to this day.

More than just a jazz album, Kind of Blue serves as the portal for so many who come to jazz for the first time. Its lasting value lies not only in its musical achievement but in its role as a gateway to understanding jazz as both an art form and a cultural expression. In an era of rapid musical change, Davis and his assembled masters created something timeless—a recording that continues to inspire musicians and listeners more than six decades after its creation.

Here’s a rare live recording from Birdland of ”So What,” a few months before Kind of Blue was released.

August 25, 1959, Birdland, New York City, New York. Miles Davis (tpt); Cannonball Adderley (as); John Coltrane (ts); Wynton Kelly (p); Paul Chambers (b); Jimmy Cobb (d)

Outstanding live version, wow, have never heard that one! Any idea what the second tune is? And a great recap to what makes jazz jazz..🙏🏽

Thanks. Good piece!