For those who prefer the Classic Comic Book version: An anonymous, sleepless narrator delivers a paranoid yet razor-sharp “midnight manifesto” diagnosing 2025 as the “Age of the Comfortable Coma,” where human thought has traded its wild unpredictability for algorithm-fed conformity. Drawing on Chomsky, Kahneman, Wolf, and others, he argues that breaking free requires courage, vigilance, and the daily practice of choosing clarity over comfort—because the most terrifying truth is that we’ve become our own wardens, and only we can cut the strings.

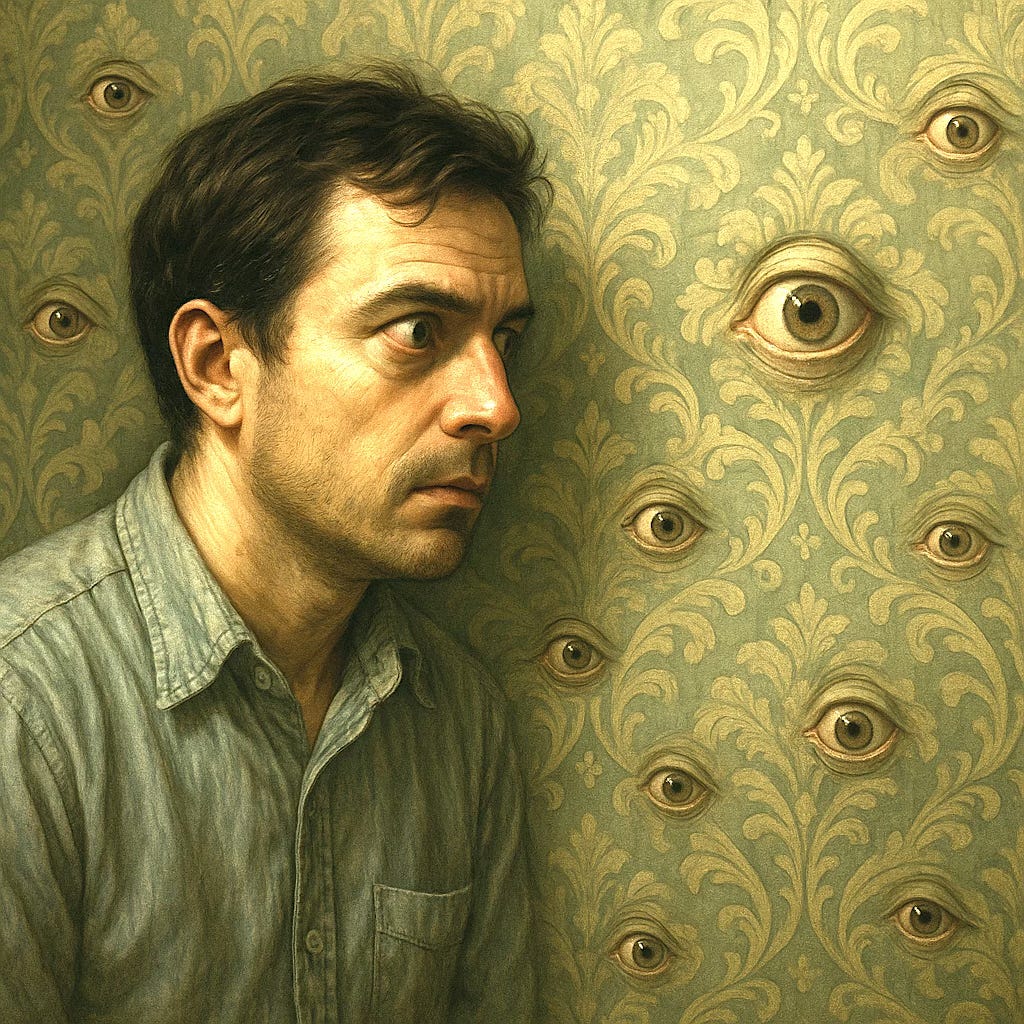

4:17 a.m. and the wallpaper is watching me.

I found myself reading these words in a document that landed on my digital doorstep like a message in a bottle from some alternate dimension where Hunter S. Thompson had lived to see TikTok. The author—anonymous, sleepless, running on fumes and fury—had captured something I'd been feeling but couldn't quite articulate: that creeping sense that we're all living through the slow-motion collapse of human thought itself.

But let me back up. Let me tell you why this midnight manifesto, with its paranoid energy and caffeinated rage, might be the most important thing you read about the state of human consciousness in 2025.

The piece opens with our narrator—let's call him the Insomniac—staring at hotel wallpaper at 4 a.m., convinced the floral lizards are taking notes. It's the kind of detail that makes you wonder if this is fiction, memoir, or something more unsettling: prophecy. But the paranoia isn't random. It's surgical. It's aimed at something very real and very dangerous.

"This is it. The Age of the Comfortable Coma. The global consciousness on Xanax, scrolling itself to death while the air smells faintly of sugar and burning wires."

The "Comfortable Coma" isn't hyperbole—it's diagnosis. We've traded the "dangerous, lush, unpredictable" jungle of human thought for what the Insomniac calls "an airport food court at 3 a.m." Fluorescent. Predictable. Safe. Dead.

Think about the last time you had a genuinely original thought. Not a reaction to someone else's tweet. Not a recycled opinion from your preferred news source. Not a meme-adjacent observation. A real, from-scratch, never-been-thought-before idea. Can't remember? Neither can most of us. And that should terrify us more than any conspiracy theory.

What makes this manifesto more than just caffeinated ranting is how it grounds its paranoia in legitimate scholarship. The Insomniac name-drops Chomsky, Kahneman, Maryanne Wolf, John Taylor Gatto—serious thinkers who've spent decades documenting how our information environment is rewiring our brains.

Noam Chomsky's "Manufacturing Consent" warned us about media manipulation decades before social media existed. But even Chomsky probably didn't imagine we'd willingly carry the manipulation device in our pockets, checking it 96 times per day like digital prayer beads. The Insomniac calls it "mental taxidermy—stuffing the skull with slogans and propping it up to look alive."

Daniel Levitin's research shows we process five times more information now than we did a few decades ago. But information isn't wisdom. It's not even knowledge. Most of it is just noise—the "pre-chewed thought-slurry" that algorithms ladle into our skulls while we scroll ourselves into oblivion.

Maryanne Wolf's work on "deep reading" reveals something even more disturbing: we're literally losing the neural pathways that allow for sustained, complex thought. The Insomniac confesses to checking his phone between paragraphs while trying to read a novel. Sound familiar? We've fracked our own attention spans dry, and we're running on fumes.

Perhaps the most damning indictment comes via John Taylor Gatto, the former New York State Teacher of the Year who spent his later career exposing what he saw as the true purpose of public education: not to create thinkers, but to manufacture compliant workers.

"Education? Gatto said it's not there to make thinkers—it's there to train good little factory ghosts. Memorize. Repeat. Obey. Don't ask too many questions."

This hits differently in 2025, when we can see the full flowering of what Gatto warned about. Students graduating with perfect GPAs who can't think their way out of an algorithmic paper bag. Adults who confuse having opinions with having thoughts. Entire populations trained to smell dissent like a contagious rash and recoil accordingly.

The tragedy isn't that we're stupid. We're not. The tragedy is that we've been systematically trained not to use our intelligence. We've been domesticated, and we call it education.

The manifesto's treatment of social media is particularly brutal: "the dopamine slot machine that sells you your own reflection, filtered for maximum tribal loyalty." Marshall McLuhan's ghost, the Insomniac tells us, is screaming "The medium is the message!" but nobody can hear him over the infinite loop of TikTok audio clips.

This isn't just social commentary—it's neuroscience. Every like, share, and comment triggers a small hit of dopamine, the same neurotransmitter involved in addiction. We're not using social media; it's using us. We've become lab rats pressing buttons for pellets, except the pellets are social validation and the maze is infinite scroll.

The real genius of the system is that it doesn't feel like manipulation. It feels like connection. Community. Belonging. But belonging to what? The Insomniac suggests it's belonging to our own digital reflection, "filtered for maximum tribal loyalty." We're not connecting with other humans; we're connecting with algorithmic approximations of ourselves, designed to keep us clicking.

Daniel Kahneman's research on "fast" and "slow" thinking provides another lens through which to understand our current predicament. Fast thinking is intuitive, emotional, reactive. Slow thinking is deliberate, analytical, effortful. Both have their place, but we've become "welded into fast now, twitch-reflex mode."

Politicians love this. Marketers adore it. Keep people in fast mode and they'll buy any binary you're selling: hero/villain, us/them, Coke/Pepsi, red/blue. Complex problems require slow thinking, but slow thinking doesn't trend on Twitter.

The result is a population that's incredibly fast at processing information but increasingly slow at understanding it. We can fact-check a claim in seconds but can't sit with uncertainty for minutes. We can identify logical fallacies in other people's arguments but can't recognize them in our own. We're simultaneously overstimulated and understimulated, informationally obese but intellectually malnourished.

Irving Janis coined the term "groupthink" to describe how intelligent people in groups can make spectacularly bad decisions. But what Janis studied in corporate boardrooms and government meetings has now gone viral. Social media has turned groupthink from a bug into a feature.

The Insomniac describes witnessing it "in boardrooms, in protests, in family dinners where one rogue sentence turns the air into glass." We've all been there—that moment when someone says something that violates the group consensus and the temperature in the room drops twenty degrees.

The smart ones get infected too, because "the need to be liked outweighs the need to be right." In an attention economy, being right is less valuable than being popular. Truth is less viral than confirmation bias. Nuance is less engaging than outrage.

The result is what the manifesto calls a "plague"—the spread of intellectual conformity disguised as diversity of thought. We have more voices than ever before, but they're all saying increasingly similar things to increasingly similar audiences.

Here's where the manifesto gets really interesting. The Insomniac argues that critical thinking isn't hard because it's complicated—it's hard because it's dangerous:

"It will strip your ego, exile you from the tribe, leave you naked in the cold with nothing but your own questions for warmth."

This is the cosmic joke at the heart of our information age. We have access to more knowledge than any generation in human history, but knowledge without the courage to think independently is just sophisticated ignorance. We can Google anything, but we've forgotten how to wonder about everything.

Erich Fromm wrote about how we surrender our freedom to avoid uncertainty. Carl Jung warned that we'll do anything to avoid facing our own souls. The Insomniac, channeling both, suggests that our digital age has simply automated these ancient human tendencies. Why face uncertainty when the algorithm will tell you what to think? Why confront your shadow when you can project it onto your political opponents?

Critical thinking, in this view, isn't just an intellectual skill—it's a form of spiritual rebellion. It's choosing discomfort over convenience, questions over answers, truth over tribe.

But the manifesto doesn't end in despair. Instead, it offers something like hope—not the saccharine kind, but the gritty, hard-earned variety that comes from crawling through the sewage pipe of your own conditioning.

"Critical thinking is a jailbreak. It's crawling through the sewage pipe of your own conditioning and coming out the other side smelling like hell but finally free."

The revolution, we're told, won't be televised or tweeted. It'll happen "in the silence between thoughts, in the space where you finally decide to think for yourself." This is both inspiring and terrifying—inspiring because it suggests individual agency, terrifying because it places the responsibility squarely on each of us.

The Insomniac offers practical advice: read a book cover-to-cover without checking your phone. Listen to people you disagree with—not to destroy them, but to understand them. Treat consensus like a bad motel—check under the mattress before you sleep in it. Each act of intellectual independence loosens the puppet strings a little more.

Perhaps the most chilling insight in the entire manifesto comes near the end:

"And then you notice the most terrifying thing: it's not them pulling the strings anymore. It's you. You've been your own warden all along."

This is the real horror—not that we're being manipulated by shadowy forces, but that we've internalized the manipulation so completely that we don't need external wardens anymore. We police our own thoughts, censor our own doubts, suppress our own questions. We've become collaborators in our own intellectual imprisonment.

But this realization is also liberating. If we're our own wardens, we can also be our own liberators. Every time we choose "clarity over comfort," every time we ask the uncomfortable question or sit with the uncertain answer, we take a step toward intellectual freedom.

The manifesto ends perfectly: after all this ranting about media manipulation and intellectual liberation, the TV calls the narrator's name. And they think it's lying.

This is the ultimate test of critical thinking—the ability to doubt even your own insights, to remain suspicious even of your own awakening. The paranoid style, it turns out, might be the only sane response to an insane information environment.

Or maybe that's what they want us to think.

Reading this manifesto in 2025 feels like receiving a message from the front lines of a war most people don't even know they're fighting. The war for human consciousness. The battle for the right to think independently in an age of algorithmic influence.

The Insomniac's vision is dark but not hopeless. It suggests that individual consciousness can still break free from collective programming, that critical thinking can still cut through the noise, that authentic human thought can still emerge from the digital cacophony.

But it requires vigilance. It requires courage. It requires the willingness to smell like hell in order to be free.

The lizards are still in the wallpaper, still taking notes. The TV is still calling our names, still probably lying. But maybe—just maybe—we're finally starting to notice.

And that noticing, that small moment of awareness between stimulus and response, might be where the real revolution begins.

The wallpaper doesn't have to win. But only if we remember how to look away.

P.S. I am the Insomniac.

My problem is that substack is quickly becoming just another part of the drug. The one, i think it's from "Brave New World", what you're describing. I'm dropping subscriptions and follows day by day. I'm hanging on to you, you're where i started. BTW, do you remember a guy from the city named Arnie Lawence?

Very good.